Summary

There appear to be no long-term studies of people who do serious strength training or powerlifting in particular after joint replacement.

Current total knee replacement prostheses utilizing ultra-high molecular weight polyethylene bearings can be expected to last more than 20 years, with a cumulative rate of revision surgery of less than 10% at 20 years.

Polyethylene wear due to contact pressure and other consequences of higher load force may be responsible for up to 40 to 50% of problems resulting in revision surgery.

Polyethylene wear rates appear to be well-described by Archard’s Law which states that the wear rate is essentially proportional to the contact pressure on the polyethylene surface and hence to the loading force on the joint.

From analysis of videos of my lifts, I estimate that time under a loaded bar for a single squat is around 11 seconds and for a single deadlift around 5 seconds. I have estimated the total time under loads higher than bodyweight is 10 minutes per week averaged across two of my typical powerlifting training programs for squat and deadlift. This works out at the equivalent of an additional 22 minutes per week with bodyweight load.

Based on reported average activity levels of people aged 65 and over, the additional 22 minutes under load results in an average increase in the rate of cumulative wear debris of 1-2%. This would result in a 2% increase in the expected TKR revision rate at 20 years from 8.7% to 8.9%. Calculations for hip replacement result in a similar increase in expected revision rate.

Powerlifting training after joint replacements by an experienced lifter with attention to technique and careful progression appears unlikely to significantly decrease hip or knee replacement lifetimes. Indeed, the improvements in muscular strength around these joints from training may result in less forces acting in the joint across all activities and more than offset the effects of higher loads on wear.

1. Introduction

Part 1 summarized 13 examples of deadlifts and 15 of squats after joint replacement. I found in an unsystematic search on the web and social media. Based on the reported weight lifted, I calculated that the median weights lifted (adjusted to a 1 rep max for a 50-year-old weighing 85 kg) were157 kg (squat) and 155 kg (deadlift). Of course, these are self-selected reports mostly from experienced powerlifters who lifted heavy before joint replacement.

Total joint replacement has been shown to have a negligible impact on post-op physical activity and return to more strenuous activities appears to be related more to patient’s own motivation rather than level of discomfort. Unfortunately, there is very limited research examining the impact that progressive resistance training has on total joint replacements.

There are few studies of long-term outcomes for people who take up physical activities after joint replacements. The usual advice is to avoid high impact activities like running, martial arts or squash, though there are increasing reports of people who have continued to do such activities after joint replacement. There are no long-term studies of people who do strength training or powerlifting in particular.

In this post, I examine the literature on causes of long-term failure of joint replacements and attempt to assess whether powerlifting training, particularly for the squat and deadlift, is likely to reduce longevity of total knee replacements (TKR) or total hip arthroplasty (THA).

2. Joint replacement lifetimes and causes of failure

Commonly quoted lifetimes for TKR prostheses are at least 15 to 20 years or greater in more than 85% to 90% of patients.

Based on a systematic review of national joint replacement registers containing data for 299,291 TKRs, Evans et al (2019) found that 93% of TKRs last 15 years, 90% last 20 years and 82% last 25 years. They also analysed published case series for 6490 TKRs which gave somewhat higher survival estimates, with 96% of TKRs lasting 15 years and 95% lasting 20 years. These higher estimates are likely due to the bias inherent in reporting of case series, with an over-representation of good surgeons and good results.

However, these figures represent the survival associated with implants used 15-25 years ago, and current fifth generation implants, such as the one I received, likely have somewhat higher lifetimes. For this analysis, I assume that 96% of TKRs last 15 years, 92% of TKRs last 20 years and 85% last 25 years.

Evans et al (2021) also reported TKR 10-year cumulative revision rates based on 493,710 TKRs in the National Joint Registry (NJR) for England, Wales and Northern Ireland from 2005 to 2016. For people with body mass index (BMI) in the normal range, the cumulative revision rate was 2.4%.

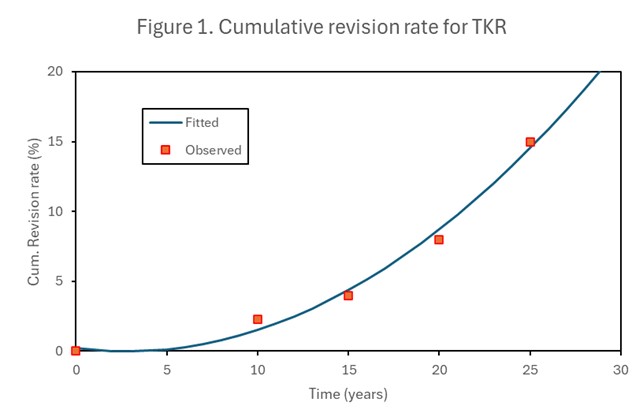

Assuming the revision rate at time t=0 is zero (we are only interested in long-term revision rates), I fitted a quadratic equation in t (years) to the combined revision rate data (see Figure 1 below). The resulting regression equation is:

Cumulative revision rate (%) = 0.22298-0.16433*t + 0.02947*t2

Over the last 30 years, ultra-high molecular weight polyethylene has been the choice of material used as bearing surfaces in total joint replacements (TJRs). It is renowned for its toughness, low friction and biocompatibility.

The most common causes of early failure and need for revision surgery (< 2 years after initial surgery) are infection and instability. More than 2 years after primary implantation, the most common causes of failure are polyethylene wear and aseptic loosening (Mulcahy et al 2014).

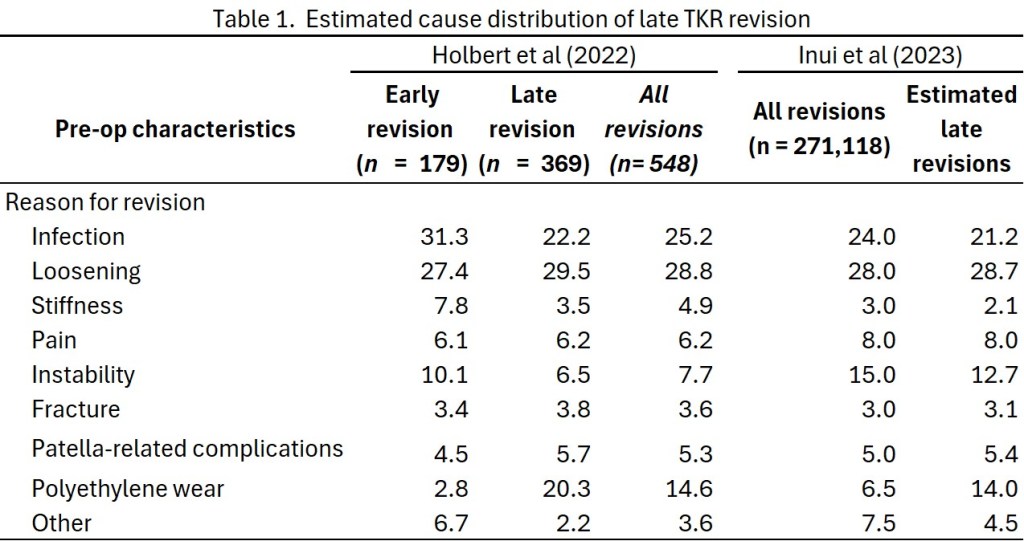

Inui et al (2023) analysed causes of TKR failure in 271,118 TKRs using data from national registries of 11 countries. Holbert et al (2022) examined the cause distribution of TKR failure for early (<=2 years) and late (>2 year) revisions in 548 patients who underwent revisions in a single hospital. The overall cause distribution was very similar to that found by Inui et al (2023), so I have used the combined data to estimate the cause distribution of late revisions in the Inue dataset (see Table 1).

As I discuss in the following section, polyethylene wear is directly proportional to the pressure on the polyethylene as the metal prosthesis slides on it. Powerlifting squats and deadlifts will increase the pressure on the polyethylene and hence increase wear. I was unable to find any quantitative analysis of the impact of load on other causes of TKR failure, though various authors noted that the buildup of wear debris in the joint contributes to the risk of infection and loosening. Fracture risk may also have a component related to load.

For my analysis, I have assumed the following proportions of late TKR failures are attributable to load on the joint for the various causes: 100% polyethylene wear, 67% loosening and fracture, 50% for patella-related complications, 33% for instability and 25% for infection. This results in an overall 50% of late TKR failures attributable to load. This is likely on the high side, and a reasonable low-end estimate might be around 25%. It is quite similar to the finding of Toh et al (2022) that 45% of hip failures were associated with wear.

3. The relationship between load and rate of polyethylene wear

Most of the literature modelling or analysing data on polyethylene wear rates in joint prostheses is based on an equation was known as Archard’s wear law (Archard 1953), which relates the wear rate R of the polyethylene to the load W (weight):

R(W) = c K W

where K is the wear coefficient, W is the load force in Newtons and c is a constant that depends on the shape, hardness, density and elasticity of the polyethylene surface (Frérot et al 2018). The wear rate R is the volume of wear debris divided by the sliding distance.

The wear coefficient is also a function of load W. At low loads, there is essentially no wear and this transitions at around 2-3 MPa. Above this contact pressure, K decreases very slowly as a function of pressure (or load) and can be treated as essentially constant (Vassiliou and Unsworth 2004, Frérot et al 2018, Dreyer et al 2022, 2023).

Archard’s law-based wear estimates represents a composite measure, incorporating the effects and relative contributions of kinematics and contact pressure. Predicted wear is generally in reasonable agreement in trend and magnitude with experimental results and clinical retrieval data (Hegadekattea 2006, Pal et al 2008). However, it is apparent from the literature that the wear process is not well understood, and it is possible that wear rates under high load may depart from Archard’s law.

4. Forces operating on knee joints during various activities including the squat

Heinlein et al (2009) measured the forces acting on a total knee joint replacement during walking, stair climbing and stair descending. The highest mean force acting in the axial direction during level walking was 276% of bodyweight. During stair climbing this increased to 305% bodyweight and during stair descending even higher forces of 352% bodyweight.

Avoiding deep flexion is often recommended by doctors and physios to minimize the magnitude of knee-joint forces. A literature review of 164 articles carried out to assess this recommendation (Hartmann et al 2013) found that the highest compressive forces and stresses are seen at a knee flexion of 90°. Beyond 90°, soft tissue contact between the back of the thigh and calf, along with functional adaptions, results in enhanced load distribution and lower compressive forces. Half and quarter squat training with the same load as for deep squats will favour degenerative changes in the long term. The authors concluded that concerns about degenerative changes in the knee joint due to squatting beyond 90° are unfounded. Provided that technique is learned accurately under expert supervision and with progressive training loads, the deep squat presents an effective training exercise for protection against injuries and strengthening of the lower extremity. Contrary to commonly voiced concern, deep squats do not contribute increased risk of injury to passive tissues.

Another paper measured net peak external knee flexion moments in untrained lifters and found that these were highest for squats below parallel, unless the thigh was in contact with the calf (Cotter et al 2013). The authors noted that a number of technique differences between elite powerlifters and low-skill lifters have been observed and that their findings may only apply to beginners and recreational squatters.

5. Forces operating on hip joint during various activities including the squat

Haffer et al (2022) used instrumented hip implants to measure in vivo joint loads during a number of exercises, including the leg press machine. Force (Fres), bending moment (Mbend), and torsional moment (Mtors) were evaluated during the training on a leg press machine with backrest positions 10°, 30°, and 60°; and loads of: 50, 75, and 100%BW (bodyweight). These loads were compared with the loads during walking on a treadmill at 4 km/h, where a median peak value of Fres 303%BW was found.

For the leg press, the median peak values for Fres, Mbend, and Mtors in all backrest positions and load conditions were significantly smaller than during walking. During the various modes of the leg press exercises, median peak values of Fres between 143 and 260%BW (10° backrest), 168 and 230%BW (30° backrest), and 147 and 227%BW (60° backrest) were measured. The authors concluded that the investigated gym machines can be considered as low-impact sports and thus as safe physical activity after total hip replacement.

Bergmann et al (2016) measured loads acting in hip implants during a number of activities, including walking and knee bends (bodyweight squat). Measured loads were linearly adjusted from the subjects’ bodyweights to an average European bodyweight of 75 kg for people aged 60 and over. The average load across the exercise period was 735 N for standing still, 1925 N for walking and 1699 N for knee bends. The peak value observed across all individuals was slightly higher for the knee bends (3145 N) than for walking (2880 N).

6. Relationship between bodyweight and polyethylene wear in total joint replacements

The weight of patients has not been demonstrated to have a consistent effect on the rate of polyethylene wear in clinical studies of total joint replacement. McClung et al (2000) found that higher body mass index (greater obesity) was associated with lower activity, and this may counterbalance the effect of the increased mass on joint wear.

Knee replacement

Gøttsche et al (2019) analysed Danish national data on all primary total knee replacements carried out during 1997-2015. They examined the association between bodyweight and time to first revision of the knee replacement. Patients weighing more than 90 kg had the highest cumulative incidence of all-cause revision during follow-up, whereas patients who weighed 60–69 kg had the lowest cumulative incidence of revision (see Figure 2).

I estimated the cumulative incidence rate (cir) at 17 years by bodyweight class, using smoothed data for years 15-18 from the graph above. I fitted a linear regression to the data for weight classes 60-69 kg and above, using the midpoint weight for each weight class and 108 kg for the 100-200 kg class. This resulted in the following estimated relationship:

cir at 17 years (%) = =-2.34 + 0.1295*bodyweight

The overall average cir at 17 years for all weight classes is 8.6% which compares reasonably well with the reported revision rates based on registry data of 7% and 15 years and 10% at 20 years (Evans et al, 2019).

Hip replacement

The National Health Service of the UK (NHS) found that 45% of total hip replacement failures in 2019 were caused by wear which led to a multitude of failures such as infection, aseptic loosening and dislocation such that a revision surgery is then needed. Toh et al (2022) developed a model of hip prosthesis wear rates associated with walking cycles that produced results comparable with previous literature. They modeled the cumulative wear in 5 million walking cycles and found that an increased bodyweight of 140 kg can increase the metallic wear by 26% and polyethylene wear by 30% when compared to 100 kg body weight.

7. Reference activity levels of people aged 65+

Dooley et al (2022) report activity patterns of older adults based on a cross-sectional study of older US adults ≥ 65 years. They report daily and hourly patterns of accelerometer-derived steps, sedentary, and physical activity behaviors. The overall average minutes per day spent in various activity categories were reported as sedentary (403 min/day), low light activity (277), high light activity (127) and moderate or vigorous activity (26).

Low light intensity physical activities include activities such as washing and drying dishes, whereas high light intensity physical activities include activities such as laundry, mopping, and walking 1.5 miles per hour (mph). I assume that low and high light intensity activities involve joint loads equivalent to 75% and 100% body weight on average, and that moderate and vigorous activities involve joint loads averaging 200% bodyweight. Thus the equivalent average minutes per day the joints are under bodyweight load are 0.75*277+127 + 2*26 = 387 minutes/day or 6.5 hours per day.

For a more conservative estimate of bodyweight activity, I only included high light intensity activities and moderate or vigorous activities. This resulted in ân equivalent daily time under bodyweight load of 2.9 hours/day.

The study also reports activity levels by BMI category. The time spent in bodyweight-equivalent load varies from 6.8 hours for normal BMI, to 6.4 hours for overweight and 5.7 hours for obese people. I assume 15% reduction in physical activity for obese (100 kg) relative to normal weight (75 kg).

8. Powerlifting training load, volume and time

I used videos of my squat and deadlift to estimate time under load through the stages of each lift. These are summarized in the following Tables. I have made simplistic calculations of the additional load associated with accelerations during each lift. These are small compared to the acceleration due to gravity (g = 980 cm/s/s) and their contribution is unimportant but I’ve carried it through.

I then consulted training diaries for a typical moderate intensity (higher volume) training program and a typical high intensity or peaking program (greater % of 1 rep max weight, lower volume). The moderate program corresponds to a weekly total volume of 11 tonnes and the peaking program to 8 tonnes per week. In a full powerlifting program there would also be tonnage associated with the bench press and some assistance exercises. These tonnages may seem low but they are probably realistic for someone like me in their early 70s at a bodyweight around 90-95 kg.

The following table shows calculations of the additional weekly load associated with a program that consisted of 50% moderate intensity and 40% high intensity training, with 10% non-training periods. This is almost certainly higher than my actual average training week and in following calculations I take the extreme case where this program continues for 20 years unchanged.

For these calculations, I assume a total bodyweight of 90 kg and that the lower limbs account for 10% of total bodyweight, so the bodyweight contribution to total weight on the knee joint in a squat or deadlift is bar weight + 80 kg. In the following calculations (Table 4), I assume that the powerlifting activity is additional to other activity (based on averages for age 65+) not replacing it. I convert total weight (wbar + 80 kg) to a multiple of bodyweight as r = (wbar + 80)/80 and then in the final column multiply the equivalent time the bar is at 1 g acceleration by r and average across the two programs to get a total additional time under bodyweight force of 22.2 minutes per week.

If I assume that this powerlifting program adds the equivalent of 22 minutes of equivalent bodyweight load per week to the average bodyweight activity time of 2.9 hours to 6.5 hours per week (under the assumptions outlined in the previous section), and that wear volume is proportional to load, then the powerlifting increases wear volume by 1% or 2% according to whether it is assumed the wear associated with other activities is the equivalent of 6.5 hours at bodyweight or 2.9 hours at bodyweight.

9. Increase in expected revision rate of TKR at 20 years due to powerlifting training

For the following calculation, I will take the higher wear estimate of an additional 2% associated with the powerlifting training program described above. The regression equation I derived for the cumulative revision rate of TKR in Section 2 gives a revision rate of 8.72% at 20 years.

An additional 2% load would result in an additional 2% accumulation of wear debris which would give a failure rate of 9.1% corresponding to that for a normal loaded TKR at 20*1.02 = 20.4 years. As discussed in Section 2, I assume that 50% of late TKR failures are associated with load, either directly or via accumulated wear debris around the prosthesis. The overall failure with the additional 2% load is 8.72/2 + 9.14/2 = 8.93% where the first term is the 50% of failures that are not load dependent and the second term is the 50% that are load-dependent. rate of 9.1% at 20.4 years. In other words the failure rate at 20 years is increased by 2% or 0.2 percentage points. An alternate formulation of the impact of the powerlifting is that it brings the 20-year failure rate forward by 0.2 years or 2.4 months.

Clearly, even with substantial variations in the main inputs to this calculation, the impact of power-lifting training for someone over 65 squatting and deadlifting in the range of 100-200% of bodyweight will not be of concern, under the assumptions around wear and failure I have used.

If, on the other hand, there is a failure mechanism that is highly non-linear with load, there could be major effects on failure rates. This could occur, for example, if there was a threshold at, say, 250% bodyweight where the wear of polystyrene changed drastically so substantial damage to the polystyrene occurred. I found no mention of any such highly non-linear mechanisms in the literature I have reviewed, nor any reports of it in any of the cases of powerlifting after joint replacement that I summarized in Part 1.

I was also reassured the studies that found that the forces involved in squatting with up to 1 bodyweight additional load were not as high as the forces involved in walking in most cases, for experienced lifts with good technique (that’s me). My squat has actually improved post-knee replacement, as I have paid very close attention to technique and to slow progressive overload.

What about the hip replacement?

In Section 6, I noted that Toh et al (2022) found that 45% of hip failures were associated with wear, and that an increased bodyweight of 140 kg can increase polyethylene wear by 30% when compared to 100 kg body weight.

Assuming wear increases linearly with load, that means that a 90 kg powerlifter with a bar weighing 90 kg would have wear increased by 67.5% while under load.

Carrying out similar calculations for hip prosthesis wear as those in Table 4 for TKR results in an estimated extra 17 minutes additional equivalent bodyweight load per week for powerlifting training which is quite similar to the additional time of 22 minutes per week for the TKR. Given the uncertainty levels of the various inputs to these calculations, I think all we can conclude is that the available data are consistent with powerlifting resulting in similar very small increases in failure rates for hip and knee prostheses.

There is evidence that musculature surrounding a TKR often remains weaker when compared to age-matched non-operated controls and to the unoperated knee (Petrizzo 2020). This persists even after several years and can be problematic as it has been found that subjects with weak knee extensors apply greater load to the knee joint during walking and other activities when compared to subjects with stronger knee musculature. So, it is possible that the benefits of strength-building of regular powerlifting training may reduce the overall daily load on the joint and compensate for the additional load from training.

Powerlifting training after joint replacements by an experienced lifter with attention to technique and careful progression appears unlikely to significantly decrease hip or knee replacement lifetimes. Indeed, the improvements in muscular strength around these joints from training may result in less forces acting in the joint across all activities and more than offset the effects of higher loads on wear.

References

Archard JF (1953). Contact rubbing of flat surfaces. J. Appl. Phys. 1953, 8, 981–988.

Bergmann G, Bender A, Dymke J, Duda G, Damm P. (2016) Standardized Loads Acting in Hip Implants. PLoS One. 2016 May 19;11(5):e0155612. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0155612.

Cotter JA, Chaudhari AM, Jamison ST, Devor ST (2013). Knee joint kinetics in relation to commonly prescribed squat loads and depths. J Strength Cond Res. 2013 Jul;27(7):1765-74. doi: 10.1519/JSC.0b013e3182773319.

Dooley EE, Pompeii LA, Palta P, Martinez-Amezcua P, Hornikel B, Evenson KR, Schrack JA, Pettee Gabriel K. Daily and hourly patterns of physical activity and sedentary behavior of older adults: Atherosclerosis risk in communities (ARIC) study. Prev Med Rep. 2022 Jun 9;28:101859. doi: 10.1016/j.pmedr.2022.101859.

Dreyer MJ, Taylor WR, Wasmer K et al (2022). Anomalous Wear Behavior of UHMWPE During Sliding Against CoCrMo Under Varying Cross-Shear and Contact Pressure. Tribol Lett 70, 119 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11249-022-01660-w

Dreyer MJ, Nasab SHM, Favre P, Amstad F, Crockett R, Taylor WR, Weisse B (2023). Experimental and computational evaluation of knee implant wear and creep under in vivo and ISO boundary conditions. medRxiv preprint doi:. https://doi.org/10.1101/2023.05.09.23289712 Preprint not yet peer-reviewed. this version posted May 11, 2023

Evans JT, Walker RW, Evans JP, Blom AW, Sayers A, Whitehouse MR (2019). How long does a knee replacement last? A systematic review and meta-analysis of case series and national registry reports with more than 15 years of follow-up. Lancet. 2019 Feb 16;393(10172):655-663. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(18)32531-5.

Evans JT, Mouchti S, Blom AW, Wilkinson JM, Whitehouse MR, Beswick A, et al. (2021). Obesity and revision surgery, mortality, and patient-reported outcomes after primary knee replacement surgery in the National Joint Registry: A UK cohort study. PLoS Med 18(7): e1003704. https://journals.plos.org/plosmedicine/article?id=10.1371/journal.pmed.1003704

Frérot L, Aghababaei R, Molinari JF (2018). A mechanistic understanding of the wear coefficient: From single to multiple asperities contact. Journal of the Mechanics and Physics of Solids. 2018 May 1; 114: 172-84.

Gøttsche D, Gromov K, Viborg PH, Bräuner EV, Pedersen AB, Troelsen A (2019). Weight affects survival of primary total knee arthroplasty: study based on the Danish Knee Arthroplasty Register with 67,810 patients and a median follow-up time of 5 years. Acta Orthop. 2019 Feb;90(1):60-66. doi: 10.1080/17453674.2018.1540091.

Haffer H, Bender A, Krump A, Hardt S, Winkler T, Damm P. Is Training With Gym Machines Safe After Hip Arthroplasty?-An In Vivo Load Investigation. Front Bioeng Biotechnol. 2022 Mar 24;10:857682. doi: 10.3389/fbioe.2022.857682.

Hartmann H, Wirth K, Klusemann M (2013). Analysis of the load on the knee joint and vertebral column with changes in squatting depth and weight load. Sports Med. 2013 Oct; 43(10): 993-1008. doi: 10.1007/s40279-013-0073-6.

Hegadekattea V, Huber N, Krafta O (2006). Modeling and simulation of wear in a pin on disc tribometer. Tribol. Lett. 2006, 24, 51–60. doi: 10.1016/j.clinbiomech.2009.01.011. Epub 2009 Mar 13.

Heinlein B, Kutzner I, Graichen F, Bender A, Rohlmann A, Halder AM, Beier A, Bergmann G (2009). ESB Clinical Biomechanics Award 2008: Complete data of total knee replacement loading for level walking and stair climbing measured in vivo with a follow-up of 6-10 months. Clin Biomech 2009, 24(4):315-26. doi: 10.1016/j.clinbiomech.2009.01.011

Holbert SE, Brennan J, Cattaneo S, King P, Turcotte J, MacDonald J. Trends in the reasons for revision total knee arthroplasty. Journal of Orthopaedics, Trauma and Rehabilitation. 2024;31(1):1-8. doi:10.1177/22104917231176573

McClung CD, Zahiri CA, Higa JK, Amstutz HC, Schmalzried TP (2000). Relationship between body mass index and activity in hip or knee arthroplasty patients. J Orthop Res. 2000 Jan;18(1):35-9. doi: 10.1002/jor.1100180106.

Mulcahy H, Chew FS. Current concepts in knee replacement: complications. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2014 Jan;202(1): W76-86. doi: 10.2214/AJR.13.11308

Pal S, Haider H, Laz PJ, Knight LA, Rullkoetter PJ (2008). Probabilistic computational modeling of total knee replacement wear, Wear, 2008, 264 (7–8), 701-707, https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0043164807005753

Petrizzo J. Training and the artificial joint. Starting Strength, 20 May 2020, https://startingstrength.com/article/training-and-the-artificial-joint

Toh SMS, Ashkanfar A, English R, Rothwell G (2022). The relation between body weight and wear in total hip prosthesis: A finite element study. Computer Methods and Programs in Biomedicine Update, 2022, 2: 100060. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cmpbup.2022.100060

Vassiliou K, Unsworth A. (2004) ’Is the wear factor in total joint replacements dependent on the nominal contact stress in ultra-high molecular weight polyethylene contacts ?’, Proceedings of the I MECH E part H : journal of engineering in medicine., 218 (2). pp. 101-107. http://dx.doi.org/10.1243/095441104322983997