What is the role of meditation and other first-person evidence in understanding the nature of consciousness and addressing the hard problem of consciousness?

I have been directly exploring the nature of consciousness for over 30 years, primarily through meditation, but also through self-hypnosis, breath work, and psychedelics. About three years ago, I decided to explore in more depth what neuroscientists and philosophers had to say about consciousness, to complement and possibly revise what I had learnt through direct experience. From mid-2022 to present, I have published nine posts on consciousness here summarizing my readings in neuroscience and philosophy, and their impact on my own understanding of consciousness. Links to these are given at the end of this post.

Neuroscientists and first-person evidence

Consciousness is a first-person experience and can only be examined directly by each person individually. My conscious experience cannot be directly observed by anyone else. In contrast, neuroscience and science in general work with third-person objective observations and measures, which can in principle be made by anyone. It can thus only deal with the correlates of conscious experience.

Neither of the two professional neuroscientists I read in detail examined evidence from meditation or research on non-ordinary states of consciousness. Anil Seth was at least up front in saying the hard problem was beyond the scope of neuroscience and that he would focus on the “easy problem” (see here). Robert Sapolsky (Determined) is focused on the issue of whether we have free will. Consciousness is relevant to that, as it may be the place where “free” decisions can be made. But Sapolsky says clearly that he doesn’t understand what consciousness is and can’t define it. He says that he can’t understand what philosophers write about it, nor for that matter neuroscientists, except in the boring neurological sense of conscious versus unconscious. He does not mention meditation or psychedelics at all, apart from a single mention of psilocybin’s effect on neurotransmitters.

Philosophers and first-person evidence

Daniel Dennett thought that consciousness itself was an illusion. It is not surprising that he totally ignored all evidence from first-person experiences apart from his own unquestioned and un-evidenced assumptions (for example, that humans, cats and dogs were the only animals that could enjoy what they do).

David Chalmers is the philosopher who invented the term “the hard problem” and understands more clearly than most that this issue is hard because it relates to the existence and/or emergence of first-person experience. I was stunned to discover that his 414 page book, The Conscious Mind, ignores first-person evidence, and the entire knowledge base on states of consciousness, meditation, non-dual states, etc.

Digging a little deeper, I discovered that Chalmers seems to have no real experience of meditation. In a 2017 interview with Chalmers, John Horgan reported that Chalmers has “never had the patience” for meditation, and he has doubts about basic Buddhist claims, such as anatta, the doctrine that the self does not really exist.

I find this astonishing. Chalmers has made the nature of consciousness his life’s work and understands intellectually that consciousness cannot be investigated using the third-person objective methods of science. But he apparently does not have the patience to investigate the results of very sophisticated methods that have been developed over thousands of years to directly investigate the nature of consciousness. While Chalmers is entirely free to doubt that the self does not really exist, it seems enormously arrogant to do this while dismissing the no-self experiences of many people, including myself, through meditation or through exploration with psychedelics. He is also ignoring the evidence from neuroscience (see Seth for example).

I have noticed that philosophers are often arrogant: treating their assumptions as self-obvious starting points rather than examine the evidence from first-person reports. The penny dropped recently that this type of philosophy reminded me of religious apologetics, arguments for the existence of a god, that all start from a set of unquestioned assumptions, rather than from evidence.

I understand the purpose of much philosophy is to explore the logical consequences of a set of values or assumptions. When it comes to metaphysics and the nature of reality, there is still a role for analytical philosophy in exploring the implications of hypothesised facts or the implications of various evidence, including first-person evidence. Chalmers and almost all the philosophers I have come across do not do that. They ignore much of the evidence and start from sets of assumptions. Such an approach is as unacceptable as the theist apologetics arguments that start from evidence-free assumptions.

Consciousness must be explored using evidence, not by using thought experiments of what is guessed to be logically possible. The primary evidence is direct personal exploration of consciousness through tools like meditation, breath work, psychedelics. None of which Chalmers appears to have any interest in or experience with.

Sure, these first-person experiences are more difficult to work with than the objective observational tools of current science, but philosophical thought experiments about “logically possible” worlds are even less adequate for understanding such an important aspect of our reality. Most philosophers of consciousness are Aristotle, working from assumptions about reality rather than Galileos, working from observation and experiment. Progress in understanding consciousness will require Galileos willing to study and use the first-person evidence as well as science and philosophical reasoning.

There are many aspects of consciousness that can be explored through meditative techniques. Below, I briefly discuss three important insights that meditation gives us on the nature of consciousness.

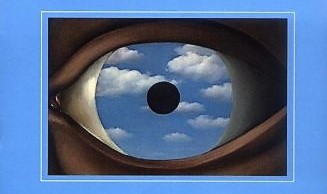

Consciousness is not the contents of consciousness

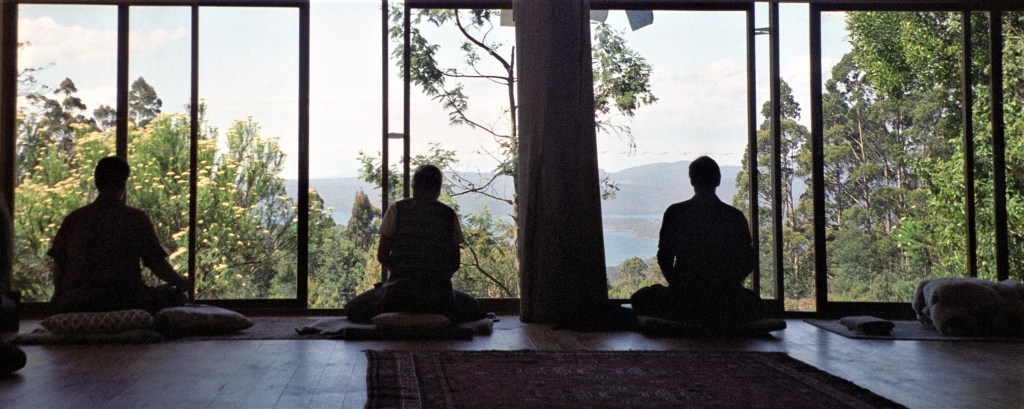

A common starting point for meditation practice is to pay attention to the contents of consciousness. Your awareness becomes an observer, separate to the contents of consciousness. Quite often a thought or sensation will grab your awareness and the next thing you know is that you have spent some time lost in a train of thought. With continued practice, you become less prone to getting lost in the contents and can watch thoughts and sensations come and go like clouds in the sky, without grasping at them.

I have learnt to become aware of my awareness, separate from the thoughts and sensory perceptions that arise in awareness. And then to take that awareness and turn it back on itself, letting thoughts and sensory perceptions fall away. While its not easy to find words that can convey a sense of that experience, there are many such descriptions in the Zen literature, for example. Awareness becomes a calm empty field of formless consciousness: body and mind dropped away.

Most of the neuroscientists and philosophers who don’t think there is a hard problem tend to equate consciousness with the contents of consciousness, most often in terms of thoughts and sensory inputs. When the contents are not present, what remains, as a matter of experience, is a field of consciousness– free, undivided, and intrinsically uncontaminated by its ever-changing contents.

The self is an illusion

Dennett asked the question “are there conditions under which life goes on but no self emerges? Are there conditions under which more than one self emerges? We can’t ethically conduct such experiments.” In fact, we can. Meditation, psychedelics, breath work and other practices can provide ethical experiments for altering brain states and consciousness. I have experienced the loss of a sense of self in meditative states, and I have experienced the emergence of multiple selves and radical changes in the sense of self while on psychedelic journeys. But that is for another post.

Sam Harris focuses on this insight, the self is an illusion, as the key insight about consciousness that meditation offers. Read his book Waking Up if you want to learn more. Briefly, in a state of pure consciousness without content, there is no sense of self. That sense is just another content of consciousness. Recent research associates this sense of self with the default mode network, the brain network thought to be responsible for autobiographical information, self-reference, and reflection on own emotions. This is the sense in which it is referred to as an illusion, woven from our individual awareness of our past, and our current thoughts, feelings and other contents of consciousness.

Anil Seth also argues that the sense of self is manufactured by the brain. He notes this is consistent with Buddhist view of no-self but sees that view as a belief, not as a result of first-person experience.

Non-dual consciousness

In everyday consciousness, the brain presents contents neatly packaged in categories, with meanings and emotions. The brain constructs conceptual boundaries between experienced qualia, the sensory inputs giving rise to those qualia and whatever is creating those sensory signals.

When consciousness turns back on itself and observes itself, there is usually still a fundamental dualism between the consciousness being explored and the observer (the mind doing the exploring). But sometimes this dualism can drop away, as can the other mental boundaries, resulting in a state of non-dual consciousness. The experience of this state is referred to as kensho in Zen, an insight or sudden awakening which may deepen with further training. Other meditation traditions and mystics may refer to this as unity consciousness, a state of being one with everything.

I have had two short tastes of non-dual consciousness. The first was spontaneous and the second occurred during a weeklong sesshin (silent retreat). My limited experience was not enough to develop an understanding of the state or its implications for the nature of consciousness. I can report that they were quite wonderful experiences and had a profound impact on me.

How are we to learn from such experiences, if we have not had any or sufficient first-person experience of them? There are many first-person accounts of such experiences in the literature of various meditative traditions. Extracting the common features of such experiences, shorn of un-evidenced metaphysical assumptions is not as easy as assessing scientific observations. This is foreign territory to most scientists and academic philosophers.

I came across an extreme example in the philosophical writings of Benjamin Cain on Medium recently. In an article on oneness with the environment, which Cain clearly had never experienced, he assumed that the ideal state sought by mystics is that of the rock that lies on the beach. The rock exists physically but has no organic properties or interior life and is simply a slave to the causal forces that act on it.

He concludes that oneness would be pure enslavement. He is an admittedly extreme example of the philosopher who is trapped in his assumptions and thoughts about a state of consciousness he has not experienced and he has not bothered to consult reports of those who have. There are many such accounts, and they report the opposite of alienation or enslavement.

I will quote just two examples from the Zen literature (for similar accounts from Christian and other mystics, see the books of Evelyn Underhill). One of the earliest accounts in English of Zen practitioners’ experiences of kensho was published by Philip Kapleau in his 1967 book The Three Pillars of Zen).

[After intense sitting with the koan mu] The next day at dokusan, the Roshi said to me “The universe is one,” each word tearing into my mind like a bullet. “The moon of truth –“ All at once the Roshi, the room, every single thing disappeared in a dazzling stream of illumination and I felt myself bathed in a delicious, unspeakable delight. American ex-businessman, age 46, 1958.

A thousand new sensations are bombarding my senses, A thousand new paths are opening before me. I live my life minute by minute, but only now does a warm love pervade my old being, because I know that I am not just my little self but a great big miraculous Self. My constant thought is to have everybody share this deep satisfaction. American schoolteacher, age 38, 1962.

Even if Cain has no personal experience or interest in reported experiences, I would expect him to have enough logical/analytical skills to guess that “oneness” of a mystic and a rock would involve a union of properties rather than an intersection of properties (ie. exclude all attributes other than those common to a rock and a person). Whatever non-dual consciousness is, and I make no claims for it here, it is definitely not just the state of being a rock.

Taking first-person evidence into account in our attempts to understand consciousness

Sam Harris (Waking Up) argues that Buddhism possesses a set of techniques and a literature on the nature of the mind that has no peer in western religion or western science. When engaged as a set of hypotheses by which to investigate the mind, Buddhist practice can be an entirely rational enterprise. Stephen Batchelor (Buddhism without Beliefs, Secular Buddhism) has advocated a secular approach to Buddhism with the same objective in mind. As has Ken Wilber in The Marriage of Sense and Soul.

To quote Harris from Waking Up: “Unlike the doctrines of Judaism, Christianity, and Islam, the teachings of Buddhism are not considered by their adherents to be the product of infallible revelation. They are, rather, empirical instructions: if you do X, you will experience Y. Although many Buddhists have a superstitious and cultic attachment to the historical Buddha, the teachings of Buddhism present him as an ordinary human being who succeeded in understanding the nature of his own mind.

“One can traverse the eastern paths simply by becoming interested in the nature of one’s own mind– especially in the immediate causes of psychological suffering–and by paying close attention to one’s experience in every present moment. There is, in truth, nothing one need believe. The teachings of Buddhism and Advaita are best viewed as lab manuals and explorers’ logs detailing the results of empirical research on the nature of human consciousness.”

Given that we can only investigate consciousness directly via first-person experience, some facts about consciousness can be discovered only from such evidence. To paraphrase Sam Harris, first-person experiences are amenable to intersubjective consensus, and refutation. Just as mathematicians can enjoy mutually intelligible dialogue on abstract ideas (though they will not always agree about what is intuitively obvious), just as athletes can communicate effectively about the pleasures of sport, meditators can consensually elucidate the data of their sphere. Such data can be objective — in the only normative sense of this word that is worth retaining — in that it need not be contaminated by dogma. As a phenomenon to be studied, meditative experience is no more refractory than dreams, emotions, perceptual illusions, or indeed, thoughts themselves.

I think its clear that the purely intellectual methods of academic philosophy will produce only limited results in understanding consciousness, as will neuroscience. I am not optimistic that the philosophers and neuroscientists will be willing to put their eyes to Galileo’s telescope and examine the night sky of consciousness for themselves. Real progress in understanding consciousness requires an integration of these fragmentary approaches with the insights to be gained from the evidence from meditation and other first-person techniques.

My previous posts on consciousness

Annaka Harris on the fundamental mystery of consciousness

Consciousness Explained or Ignored: A review of Daniel Dennett

The hard problem of consciousness: David Chalmers and The Conscious Mind

The “real” problem of consciousness: a review of Being You by Anil Seth

Consciousness and free will – Part 1

Consciousness and free will – Part 2

Beautifully written and deeply reflective. I love how you tied meditation to the direct experience of consciousness, it’s a reminder that understanding doesn’t always come through analysis, but through stillness. Looking forward to more like this!

Thank you. I’m glad you appreciated it. I am about to start work on a follow-up article, but I may take a while as summer activities distract.