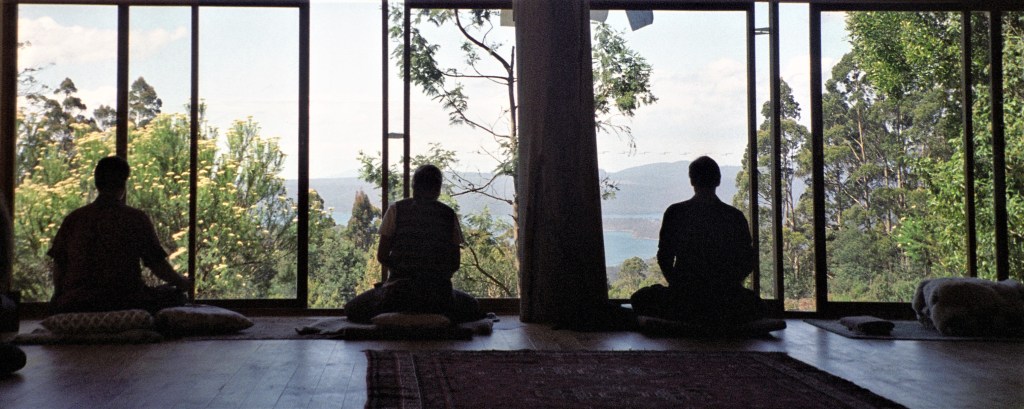

Over the last couple of years, I’ve been thinking more and more about the nature of consciousness. My Zen meditation practice basically involves letting go of thoughts, letting go of the self, and simply experiencing consciousness without content. I have direct experiences from my meditation practice, as well as a reasonably wide reading of Zen and Buddhist masters and their experiences and understanding of consciousness, self and reality. At times, I feel like I have had openings to experiences which have “enlightened” me about the nature of self, consciousness etc, but I have not really integrated these tastes of non-self into any sort of stable or mature understanding of reality.

I had read a few articles by philosophers who have explored the nature of consciousness, particularly the so-called hard problem of consciousness and last year read a review of a new book by Anil Seth which led me to think he had made advances from the neuroscience perspective.

Apart from my direct explorations through Zen meditation, breathwork and psychedelics, I also have worked with several Zen teachers and read extensively on consciousness in Buddhist literature and in the works of Ken Wilber, who has explored and mapped states and stages of consciousness in his writings. More recently, I read and reviewed Sam Harris’s book Waking Up, which also discusses the nature of consciousness and self.

So I decided I would read some of the key books and articles on consciousness from the philosophers and neuroscientists, to complement my experience and understanding gained from meditation and psychedelic explorations.

I bought the following books:

- Anil Seth. Being You : A New Science of Consciousness. Faber and Faber (2021)

- Peter Godfrey-Smith. Metazoa: animal minds and the birth of consciousness. William Collins (2020)

- Harris, Annaka. Conscious: a brief guide to the fundamental mystery of the mind. Harper 2019. Kindle Edition.

- David Lewis-Williams, David Pearce. Inside the Neolithic Mind: Consciousness, Cosmos, and the Realm of the Gods. Thames Hudson (2005)

- David J. Chalmers The Conscious Mind: In Search of a Fundamental Theory. Oxford University Press 1996

- Daniel Dennett. Consciousness Explained. Penguin (1993).

- Derek Parfit. Reasons and Persons. Oxford University Press (1986)

Anil Seth is a neurologist, Peter Godfrey-Smith a biologist and philosopher of science. Annaka Harris is a science writer (fun fact: also the wife of Sam Harris). Lewis-Williams and Pearce are both archaeologists. The final three are all philosophers. I guess the other relevant discipline I am missing is artificial intelligence research. I’ve read a little in this area and have found it mostly irrelevant to the issues relating to consciousness that I am interested in, and tedious reading to boot.

I browsed Chalmers book on consciousness and discovered the entire book ignores the entire knowledge base on states of consciousness, meditation, nondual states, etc. As if it’s irrelevant. So I quickly browsed the books by the other two philosophers, and the book by Anil Seth the neurologist. Not a single mention of meditation, altered states, psychedelics. I had bigger problems with Seth’s ideas, but will leave that to a separate review.

My initial reaction was to dismiss the philosophers as inhabiting a limited sterile corner of academia ignoring large parts of human experience. But then realized if I did that, I would be no better than them.

Ken Wilber has gone down this same path of integrating Western psychology and philosophy with Eastern first-person methods and understanding and has been largely ignored by academia and philosophers. In part, because he does somewhat go over the top, and despite his focus on empirical methods, does seem to uncritically accept aspects of Tibetan Buddhism at more or less face value. Such as rebirth.

Sam Harris seems to get it more right. And his conclusions are very much aligned with mine. And even he gets dismissed by Western commentators as being arrogant. By telling them they cannot just critique from the outside, without trying the methods for themselves. So much for open-mindedness to all the relevant evidence.

For consciousness per se, which is a subjective experience, its clear that the objective methods of science are going to be at best marginally relevant. What is most relevant is the actual massive domain of experiences of consciousness. Particularly those focused not on the contents of consciousness (as the psychologists and neuroscientists like to do) but those focused on the exploration of consciousness per se when the contents are out of the way. The recent book by Anneka Harris is the only other one on my list above which examines what meditation tells us about consciousness. And when I started reading it, I found it a superb discussion of the various issues and theories about consciousness. So my next post will be a closer look at Harris’ book, and then I will dive into the philosophers.

Links to my later posts on consciousness are given below:

Anneka Harris on the fundamental mystery of consciousness Oct 6 2022

Consciousness Explained…..or Consciousness Ignored? Oct 16 2022

took a form of Christianity as a solution to existential angst. I was reminded of a book I read probably 15 years ago, by Stephen Batchelor: Buddhism Without Beliefs (London: Bloomsbury 1997) which argued that the Buddha was concerned with addressing the existential issue of suffering not with metaphysics and beliefs. I couldn’t find my copy of this, and bought another, which I enjoyed reading even more than the first time.

took a form of Christianity as a solution to existential angst. I was reminded of a book I read probably 15 years ago, by Stephen Batchelor: Buddhism Without Beliefs (London: Bloomsbury 1997) which argued that the Buddha was concerned with addressing the existential issue of suffering not with metaphysics and beliefs. I couldn’t find my copy of this, and bought another, which I enjoyed reading even more than the first time.