I recently encountered a discussion about which countries are the most and least religious. This post presents some comprehensive results for the year 2020 based on my earlier analyses of global, regional and country-level trends in religious belief and practice, and the prevalence of atheism (see earlier posts here, here, and here). These analyses used data for 110 countries from the World Values Survey (WVS) and the European Values Study (EVS), covering the period 1981 to 2020 [1-3]. In previous analyses, I defined four religiosity categories as follows:

Practicing religious person: A religious person who believes in God* and is practicing**, OR a non-religious person who believes in God, is practicing, and rates the importance of God in the top 5 points of a 10 points scale.

Non-practicing religious person: A religious person who believes in God and is non-practicing OR a non-religious person who believes in God, is non-practicing, and rates the importance of God in the top 6 points.

Non-religious: A non-religious person who believes in God but rates the importance of God as any of three points at the not important end of a 10-point scale.

Atheist: A “confirmed atheist” and/or does not believe in God

Respondents were classified as “practicing” if they attend religious services or pray to God outside of religious services at least once a month. I assigned all people who do not believe in God to the atheist category. This will include some religious people who practice non-theist religions such as Buddhism.

For this post, I decided to move the atheists who said they practiced religion at least once a month to the “practicing religious person” category. In most of the regions where the prevalence of atheism was high, the percent of atheists who are practicing religious is small, at most a few percent. Its likely these are regions where there is no stigma or danger in being atheist, and the few percent practicing are likely attending religious services with other family members who are religious. In regions where the prevalence of atheism is very low, the proportion of atheists who attend religious services is generally much higher (30-40%), almost certainly reflecting stigma and danger in being openly atheist.

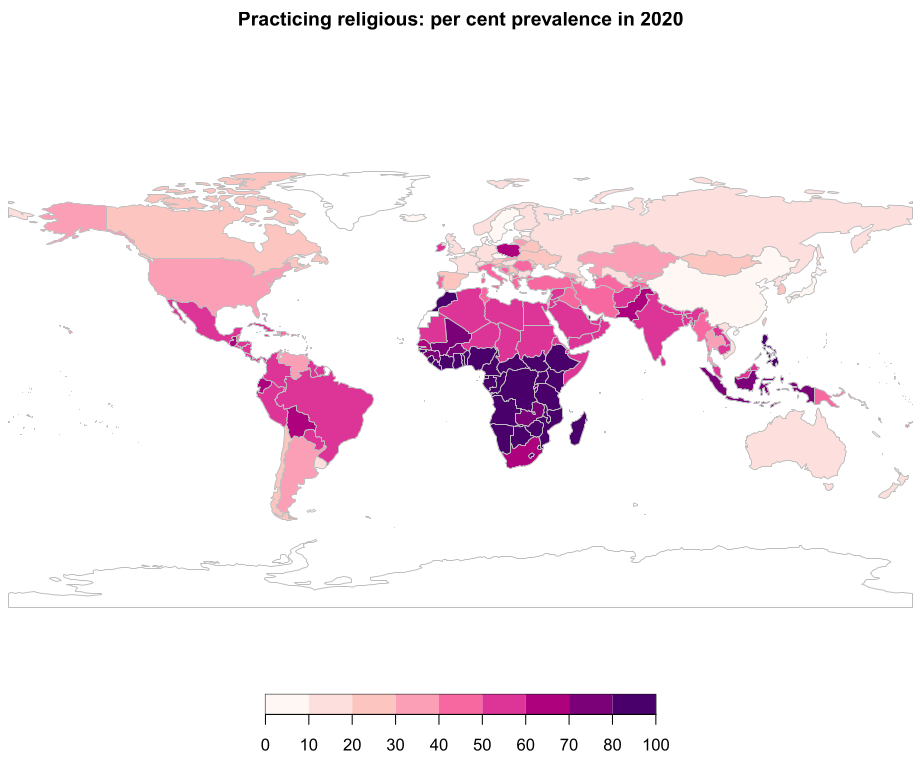

I moved the proportion of atheists who are practicing religious to the practicing religious category for the maps below. This adjustment makes little difference to the results. The first map shows the global variations in the proportion of country populations who are practicing religious.

Ethiopia is the most religious country in the world, with 93% practicing religious. Three other countries have greater than 85%; Qatar, Nigeria and Morocco. Of the 35 countries with a prevalence of practicing religious greater than 80%, 31 are in sub-Saharan Africa, two are in the Islamic east, Malta is in the Old West, and the Philippines is in the Indic East.

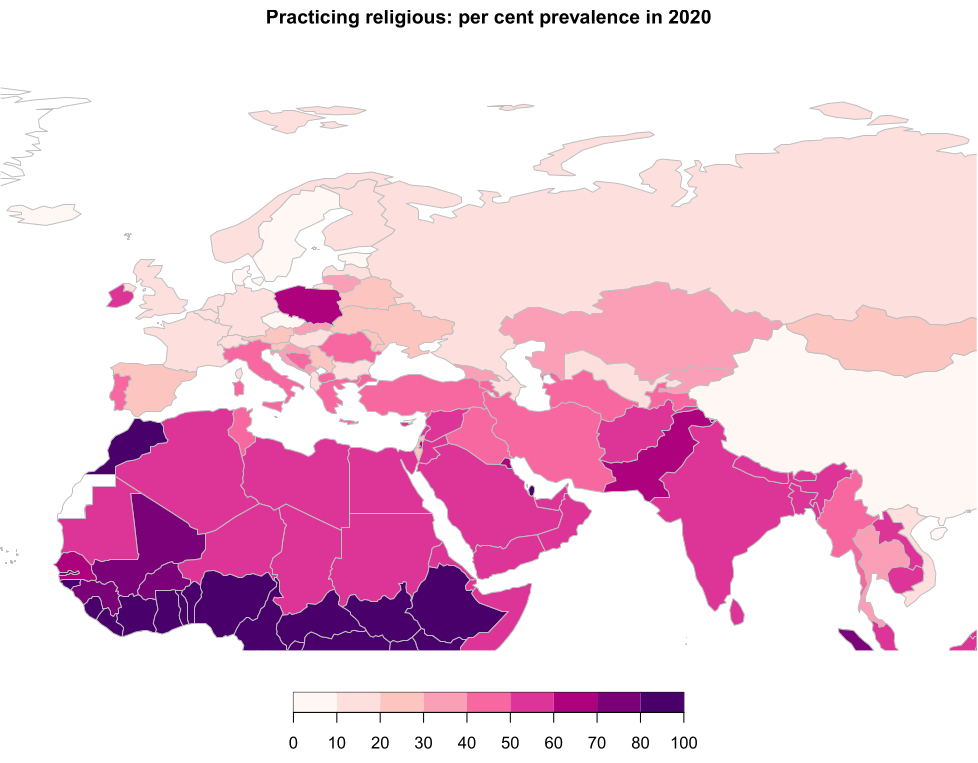

The least religious country in the world is China with only 3% practicing religious, followed by Denmark (7%), Estonia (8%), Czechia (9%) and Iceland (9%). The following map zooms in on the European and Asian regions. It can be seen that very low in most European countries, apart from some of the Mediterranean countries, Poland and Ireland.

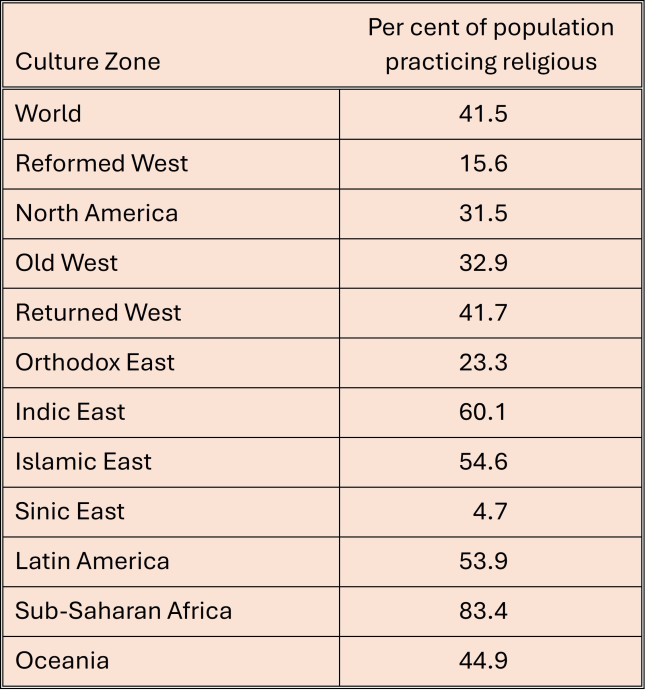

The following table summarizes the prevalence of practicing religious people by culture zone. The 11 culture zones used in this table are defined here (see endnote d).

The global average is 41.5%, If China is excluded, the global average rises to 51.5% and the Sinic East to 13.6%. As I’ve examined in more detail in a previous post, the higher the proportion of the population that is religious, the less modern are their values (see here).

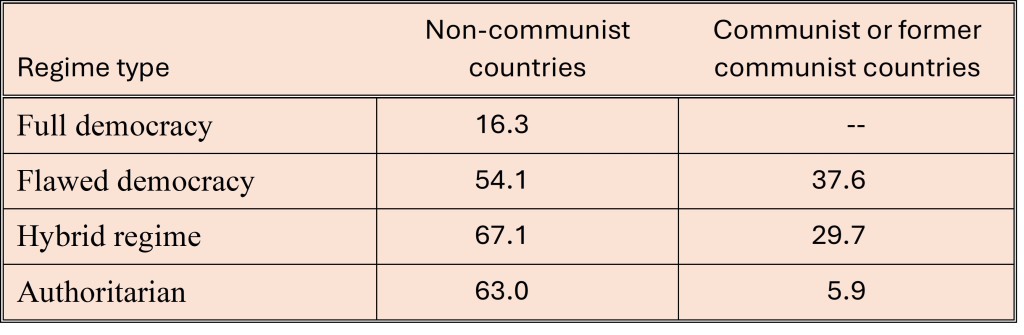

Looking at the map it struck me how, excluding China, in general the more religious regions of the world were less democratic. I took a closer look at this using the Economist magazine’s Democracy Index for the year 2020 [4]. The Democracy Index is based on five categories: electoral process and pluralism, the functioning of government, political participation, political culture, and civil liberties. Based on its scores on a range of indicators within these categories, each country is then itself classified as one of four types of regime: “full democracy”, “flawed democracy”, “hybrid regime” or “authoritarian regime”. Hybrid regimes have the appearance of democracy, but elections are not free and fair, the press is not free and the judiciary is not independent.

An initial examination of the data showed that there were a set of outliers with low prevalence of practicing religion and low democracy index values that were all current or former Communist countries. These were countries such as China, North Korea, Russia and Belarus.

I decided to tabulate the prevalence of practicing religious people by democracy category and communist history. As I expected, full democracies are characterized by low prevalence of practicing religious (16%) and other regime type by over 50% of the population practicing religious in countries without a communist history. The prevalence of religious practice in communist or former communist countries is systematically lower than in other countries across all regime types and none of these countries is a full democracy. The average prevalence is pulled down by China for the authoritarian regime type. Exclusion of China results in an average prevalence of 19.7% practicing religious in for authoritarian communist/ex-communist countries.

by regime type and communist history

I should emphasize that correlation does not per se imply causation. However, my previous analyses of the higher prevalence of pre-modern values in countries with higher levels of religiosity does supply a plausible mechanism for a causal association. Karl Marx famously said that “Religion is the opium of the people”. He was suggesting an opposite direction of causality: that religion is the solace of the oppressed, in other words that exploitation or authoritarian government caused people to turn to religion.

In an earlier post, I examined the differences in values between Democrats in blue US states and Republicans in red US states. I found that Blue-Democrats have followed a very similar trajectory to the average of Australia, New Zealand and Switzerland over the last three decades, with relatively rapidly rising levels of modernity. This puts them very much in the company of modern Western secular states. In contrast, the Red-Republicans level of modernity tracks closely the average for Russia, Poland, and China, and currently falls about halfway between that of China and Russia. This might help to explain why they are quite happy for their cult leader Trump to openly say that he will rule as a dictator and dismantle democratic voting. Pre-modern religious values are quite similar to fascist values, and Christian nationalists are clearly seeking to establish a theocratic autocracy. It seems clear that where high levels of religiosity are associated with pre-modern values, such people are pre-disposed to seek or support non-democratic forms of governance.

References

- EVS (2021): EVS Trend File 1981-2017. GESIS Data Archive, Cologne. ZA7503 Data file Version 2.0.0, https://doi.org/10.4232/1.13736

- EVS/WVS (2021). European Values Study and World Values Survey: Joint EVS/WVS 2017-2021 Dataset (Joint EVS/WVS). JD Systems Institute & WVSA. Dataset Version 1.1.0, doi:10.14281/18241.14.

- Haerpfer, C., Inglehart, R., Moreno, A., Welzel, C., Kizilova, K., Diez-Medrano J., M. Lagos, P. Norris, E. Ponarin & B. Puranen et al. (eds.). 2021. World Values Survey Time-Series (1981-2020) Cross-National Data-Set. Madrid, Spain & Vienna, Austria: JD Systems Institute & WVSA Secretariat. Data File Version 2.0.0, doi:10.14281/18241.15.

- The Economist Intelligence Unit. Democracy Index 2020: In sickness and in health? Available at https://www.eiu.com/n/campaigns/democracy-index-2020/