I’ve had a number of near-death experiences over the years. Almost all of these were the result of sheer stupidity doing risky things. I recently read an account by someone who survived having seen certain death approaching. That and other recent circumstances have got me thinking about my own experiences and meditating on death and dying more generally.

In this post I remember two incidents in which I was knocked unconscious and would never have known about it if I had died. These experiences had a far greater impact on me and my feelings about death and dying than any of the incidents where I realized that death was a probable outcome.

In the early 2000s, I was in South Africa for three weeks as one of the staff for a WHO global training course. The course was being held in a small game park and resort, which was closed to general visitors. There was a water slide which was also closed, but several of us persuaded the staff to open it one lunch time for us. The water slide was a fully enclosed tube with water running through it which ended over a small swimming pool about 2 metres deep. My friend J and I were the first two there and each did a slide down the tube. I sat up in the tube and found there was too much friction so that I went down quite slowly.

For my second slide, I lay down completely flat in the tube. I do now remember the initial moments, going quite fast and bouncing around in the tube. I must have hit my head on the side of the tube on the way down because I was unconscious when I entered the water and went to the bottom of the pool.

J had gone down before me and was already walking back up the path to the top of the slide. Halfway up he looked back and saw me lying on the bottom of the pool. He initially thought I was clowning around and kept walking. But when he looked back again, I was still in the bottom of the pool. He ran back down to pull me out of the water. I was bleeding heavily from a cut over one eye, and he told me later he thought my skull was broken and my brains were coming out. I regained consciousness a few minutes later, I don’t know whether he did resuscitation or I started breathing on my own. I asked him what happened and where was I. When he told me we were in South Africa, I was astonished. I had no memory of going to South Africa or any idea why I would be there. I was as astonished as if someone had just told me I was in Siberia. I knew who I was and who J was, but I had no memory of anything that had happened in the last few weeks.

An ambulance came, and I was taken to the nearest town with a hospital, where they took X-rays of my head and neck. And debated for some time whether the signs of fractures in my neck vertebrae were new or old (they were old). I was fitted with a neck brace and they stitched up the split skin over one eye. My amnesia gradually disappeared over a period of a day or so, until eventually I could remember the initial part of going down the slide and starting to oscillate. But the actual blow to the head and the aftermath before I came to has remained a blank.

It was an existential shock to realize that if I had not been pulled out, but drowned, I would never have known. I would not have known I was about to die. Amnesia meant my mind was a blank in the minutes leading up to possible death. It was profoundly disturbing to realize it was entirely possible I would die without ever knowing about it. And it continues to be a realization that I keep revisiting.

I also realized that the state of being dead is nothing to fear. I experienced “not being there” in any form and its nothing at all to be afraid off. You don’t exist, and there is nothing to experience the not existing.

The second experience occurred a couple of years later in Geneva. I had left work to ride to the gym on my bicycle. I was riding in the bus lane on a road which went down a long slope from the World Health Organization. I was riding quite fast and became worried that a bus might be coming up behind me. I looked back and in doing so steered the bike into the gutter. I hit the gutter at speed and went over the front handlebars.

That is the last memory I have until I suddenly became aware that I was on my bicycle and covered in blood. I was bleeding quite profusely from skin loss on legs and arms and riding in heavy traffic. I had no idea where I was at all but knew from my injuries that I must have been in some sort of accident. I got off the bike and rang my wife on my mobile. I explained I had been in an accident and had no idea where I was. She told me to go to the nearest street corner and tell her the names of the streets. I did that and it turned out I was near the main train station about three and a half kilometres from where the accident occurred.

She came and got me and took me to the hospital, where they diagnosed concussion (duhh!), cleaned and bandaged my wounds, and kept me overnight under observation. When I returned to work and told colleagues what had happened, one of them told me he had seen me on my bicycle riding in the traffic and had not noticed anything unusual. Apparently I am capable of riding in traffic while unconscious. Or perhaps conscious but without any memory-retention ability. I could easily have ridden in front of a car and been killed. As with the first experience, if that had happened I would never have known.

I guess death was a more certain possible outcome for the South African experience. If my friend had not seen me on the bottom of the pool and got me out in time, I would have almost certainly died. This was a much more traumatic experience (after the event) than other “near-death” experiences where I was conscious and realized I was likely to die. I’ll write about them in a later post.

I recently read a blog post by Nathan Hohipua in which he argues that it is impossible to (truly) imagine our deaths, and that the only possible attitude towards death is one of anxiety. He claims that “The light of consciousness cannot really, truly imagine its own extinction” and concludes that “Anxiety is the only possible response to death because it’s just what it is to contemplate something that literally can’t be contemplated because it is the end of all possibility of contemplation.“

I think he is wrong in generalizing his own inability to imagine the state of being dead to others. In the waterslide accident, I truly feel that I came back from an experience identical to that of being dead. No memory, no awareness, no experience, nothing. If I had not come back, I would never have known it. That realization has been profoundly disturbing. But the state of being dead? I experienced “not being there” in any form and its nothing at all to be afraid off. You don’t exist, and there is nothing to experience the not existing. I may be missing something, but I don’t have any problem accepting that there will be a future point after which I simply don’t exist. Its exactly the same as before the point in time at which I started to exist (some time after conception). I have not existed for billions of years and I will also not exist for billions more.

The process of gradually losing function and experiencing pain and possibly loss of mental functioning, whether through ageing or illness, that is a completely different issue. And something that does worry me. I am working on accepting and letting go of the mental drama about it. And eventually when needed, do some contingency planning and prepare a living will. Nathan Hohipua says that if someone tells you they have completely accepted their death, they are deceiving themselves. That likely is true in some cases. And might be true if you are referring to the process leading up to the point of death. But completely untrue for me, if you are referring to the state of being dead. I’ve experienced it, and its nothing to be afraid of.

The restrictions during the second wave of covid-19 have been less severe in Geneva than during the first wave, although France has closed my nearby border until mid-December and instituted strict lockdown again. However, I went to a bakery the other day and saw a notice that said people aged 65 and over were asked not to leave home. I had been keeping pretty much at home in any case, and one of the things I decided to do in this period was to see whether I could achieve WILD, ie. wake-induced lucid dreaming. I’ve previously had success with DILD (dream-induced lucid dreaming) which is the best known technique and involves becoming aware you are dreaming while you are in a dream. WILD involves transitioning directly from the hypnagogic state into the dream state while maintaining awareness throughout.

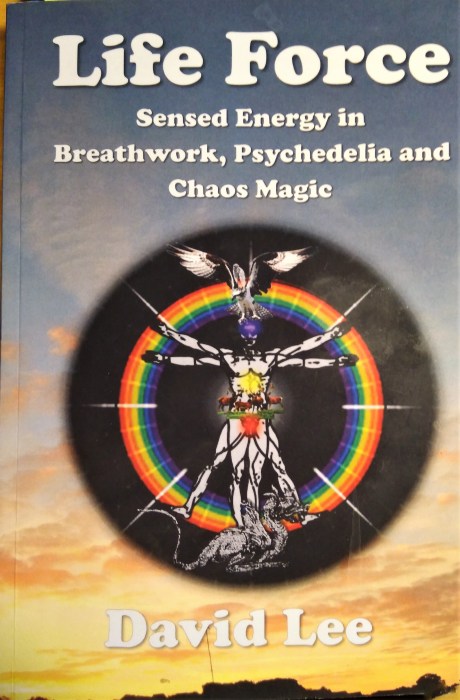

The restrictions during the second wave of covid-19 have been less severe in Geneva than during the first wave, although France has closed my nearby border until mid-December and instituted strict lockdown again. However, I went to a bakery the other day and saw a notice that said people aged 65 and over were asked not to leave home. I had been keeping pretty much at home in any case, and one of the things I decided to do in this period was to see whether I could achieve WILD, ie. wake-induced lucid dreaming. I’ve previously had success with DILD (dream-induced lucid dreaming) which is the best known technique and involves becoming aware you are dreaming while you are in a dream. WILD involves transitioning directly from the hypnagogic state into the dream state while maintaining awareness throughout. discussing their various purposes and effects, and the relationships between them. This is interesting enough, but his approach to understanding breathwork completely changed my experience of it. He describes the book as an exploration of “sensed energy” and schemes of belief that work best for experiencing, cultivating and manipulating these subtle sensations. In particular, he frames breathwork in terms of the arousal and relaxation of sensed energy.

discussing their various purposes and effects, and the relationships between them. This is interesting enough, but his approach to understanding breathwork completely changed my experience of it. He describes the book as an exploration of “sensed energy” and schemes of belief that work best for experiencing, cultivating and manipulating these subtle sensations. In particular, he frames breathwork in terms of the arousal and relaxation of sensed energy.