In my first post on near-death experiences (NDE), I recalled two incidents where I was knocked unconscious and would never have known if I had died (which was by no means unlikely). The following two incidents are quite different. In both cases I fell off a cliff and was fully conscious till I hit the ground below.

Continue readingCategory Archives: The big picture

The Wide Sky

Let me not spend my life

lamenting the world’s sorrows

for above

in the wide sky

the moon shines pure

ukiyo to mo

omoi-tōsaji

oshikaeshi

tsuki no sumikeru

hisakata no sora

— Saigyo

I came across this poem quite by accident. But it really struck home, as I’ve been spending too much time thinking about the state of the world right now. The human race appears to be quite incapable of working together to address the existential crises of the pandemic, global heating and species extinctions, and overpopulation, as well as the rejection of reason and science dramatically exacerbating these potentially soluble crises. Humans have not reacted to these crises in general by pulling together, given that collective action can indeed address and ameliorate, if not completely address, them. But ratherhave retreated back into tribes who blame the “other” for all their problems. It is indeed difficult sometimes to remember the moon shining pure in the wide sky.

Saigyō was the Buddhist name of Fujiwara no Norikiyo (1118–1190), a Japanese Buddhist monk-poet. He is regarded as one of the greatest masters of the tanka (a traditional Japanese poetic form). He influenced many later Japanese poets, particularly the haiku master Basho.

Saigyo was born into a branch of the Fujiwara clan, the most powerful family in Japan in the early 12th century. As a young man he joined the Hokumen Guards who served at the retired Emperor’s palace. Despite a seemingly assured future, he decided at the age of 23 to “turn from the world” and become a reclusive wandering Buddhist monk. He spent the rest of his life in alternating periods of travel and seclusion with occasional periodic returns to the capital at Kyoto to participate in imperial ceremonies. During this period, the second half of the 12th century, Japan was wracked by civil war

The translation of the poem above is by Meredith McKinney, who has published a selection of over 100 poems by Saigyo in the collection Gazing at the Moon: Buddhist Poems of Solitude (September 2021). The poems selected focus on Saigyo’s story of Buddhist awakening, reclusion, seeking, enlightenment and death. I can highly recommend this collection, which embodies the Japanese aesthetic of mono no aware — to be moved by sorrow in witnessing the ephemeral world.

Meredith McKinney is an award-winning translator of classical and modern Japanese literature, who lived and taught for around 20 years in Japan. She returned to Australia in 1998 and now lives near the small town of Braidwood, not far from Canberra where I lived until early 2000. I was interested to learn a little more about her, and was surprised to find out that she is the daughter of Judith Wright (1915-2000), one of Australia’s greatest poets and an activist for the environment and indigenous rights. For the last three decades of her life, Wright lived near Braidwood. She became completely deaf in 1992 after progressively losing her hearing since early adulthood.

Religiosity and atheism in younger adults

I recently came across a headline referring to a 2016 survey in Iceland which found that 0.0% of Icelanders 25 years or younger believe God created the world. My immediate impression was that this implied a zero per cent prevalence of atheism in this age group. When I read the article, I found that the relevant question gave respondents four options: the world was created in the big bang, the world was created by God, the world was created by other means, or no opinion. Outside of countries dominated by fundamentalist religious groups, most religious people would likely choose “created in the big bang”. The survey actually found that 40.5% of respondents aged 25 years and younger said they were atheist, and 42% said they were Christians.

It is certainly the case that the prevalence of atheism is higher in younger ages in the developed countries where religiosity has been declining for decades. So I thought I would take a look at the prevalence of atheism in younger adults aged 15-34 years from the Integrated Values Surveys [1-3] that took place in the last wave, in the period 2017-2020. See my earlier posts (see here and here), which examined global, regional and country-level trends in religious belief and practice, for more details on the data and definitions of atheism and religiosity categories.

Countries with the highest prevalence of atheism and non-religion in 2017-2020

The following plot shows the prevalence of religious and irreligious adults for the 31 countries with the highest irreligious prevalence (atheists plus non-religious). China and South Korea lead these countries with irreligious prevalences over 80%, followed by Sweden, Czechia, New Zealand and Japan, with prevalences in the 70’s. In terms of atheism, there are 18 countries with prevalences over 50% in the 15-34 year age group, including Australia at 53%.

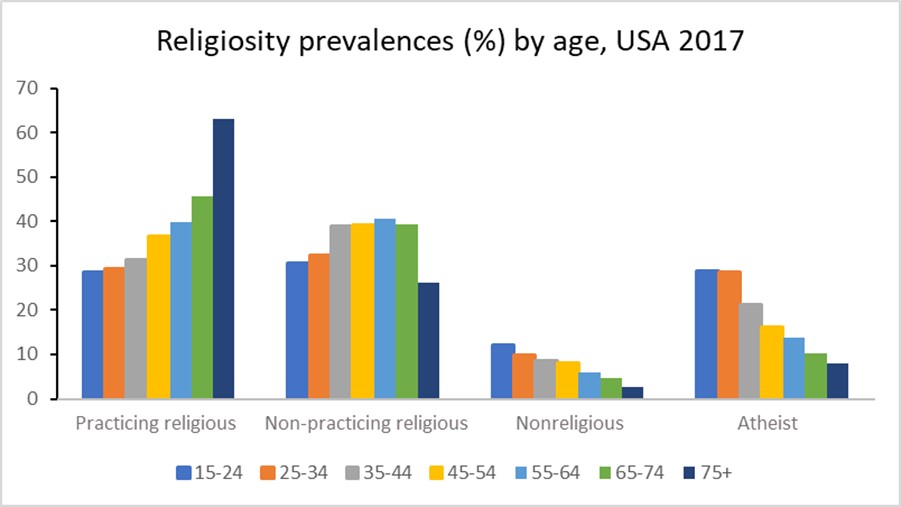

In these countries, the prevalence of practicing religious generally increases with age and the prevalence of atheists generally decreases with age. The plot for the USA 2017 survey data below illustrates this.

Are these prevalence patterns predominantly due to ageing, time period or birth cohort? Since period = birth year (cohort identifier) + age it is not possible to determine the separate effects of all three factors. Ageing as a driver of religiosity would imply that people become more religious as they get older, and this seems the least likely of the three factors to fit observed age patterns over time.

Relative contribution of cohort and period to the overall trends in religiosity

I’ve attempted to estimate the relative contributions of birth cohort and period to the evolution of religiosity in the USA using a cohort projection model. I first used the data from all waves of the US surveys to impute religiosity prevalences for years 1980, 1990, 2000, 2010, and 2020. I then projected religiosity prevalences for each age group in 2020 assuming that those prevalences remained constant at the values that age group would have had in the past when it was aged 15-24. Comparing this with the actual prevalences for 2020 allows estimation of the proportion of the change in prevalence over time that is attributable to cohort effects.

For practicing religious, non-religious and atheists, the cohort projection explains around 25% of the overall change, the other 75% is attributable to period. For the non-practicing religious, these proportions are reversed with 25% explained by period and 75% by cohort.

Projecting religiosity prevalences to 2030

My previous projections of religiosity to year 2020 were carried out using trends in all-ages-both sexes prevalences. I thought it would be interesting to explore projections at age-sex level for selected countries, given the likely variations in trends across age groups. I experimented with several statistical models including a period-cohort projection model, and a model that projected all four prevalences simultaneously, using seemingly unrelated regression techniques to constrain the prevalences to add to 100%. It proved difficult to get sensible results from these models when not tailored to specific country data. The disaggregation of survey data to 7 age groups for each sex resulted in highly variable prevalences across cells. The years for which surveys were available varied across countries in ways that made it difficult to develop generalized projection methods that were not sensitive to small number issues and outlier trends.

I eventually decided to do some quite simplistic projections for each age-sex category as follows:

- Project from last available wave to 2022 using short-term trends given by last two waves

- Project from 2022 to 2030 using longer-term trend from wave closest to year 2000 to last wave

- Adjust extreme trends to either the smaller of the short and long run trends, or to trends for neigbouring age-sex groups.

I carried out these projections for five high income countries with rising prevalence of atheism: USA, Australia, Switzerland, United Kingdom and Sweden. The following plots illustrate the observed and projected prevalences for the four religiosity categories. The dashed lines denotes the projected trend for irreligion (non-religious plus atheist).

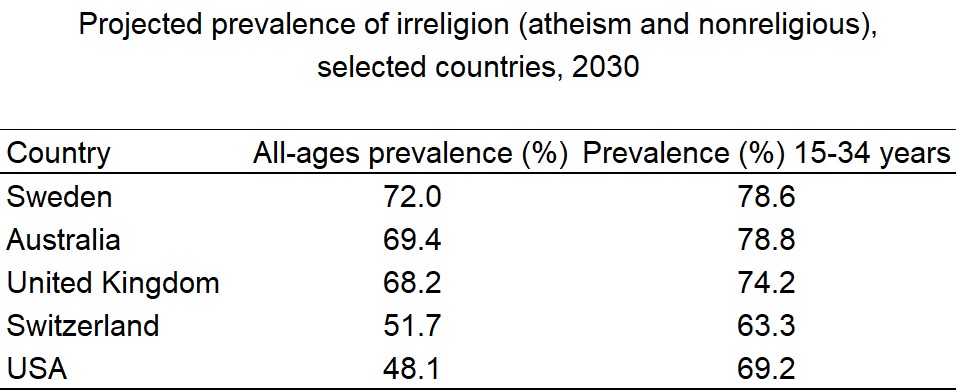

The nonreligious category includes people who state that they believe in God, but that they are non-religious and rate the importance of God as 8-10 at the not important end of a 10-point scale. In the table below, I summarize the projected prevalence of irreligion (nonreligious or atheist) in 2030 for the five countries for all ages combined and for the young adult age group 15-34 years. The irreligion prevalence is generally higher in the younger age groups, and the 2030 value gives an indication of likely future trend for all ages.

Is irreligion likely to continue increase in the future? If the economies of high income countries continue to grow, with decreasing levels of poverty, and education levels continue to improve, it is likely that religiosity in these countries will decline in the longer term. The joint global crises of global warming and the pandemic, with rising populism and rejection of global institutions and actions, may on the other hand result in economic downturns that result in a stalling or reversal of the current religiosity trends. The situation in the USA where a religious minority is actively seeking to impose its values on the entire population, and undermining the democratic system to achieve that, may likely accelerate the turning away from religion of the young adult population. The USA already has one of the fastest rates of increase of irreligion in the last decade.

References

- EVS (2021): EVS Trend File 1981-2017. GESIS Data Archive, Cologne. ZA7503 Data file Version 2.0.0, https://doi.org/10.4232/1.13736

- EVS/WVS (2021). European Values Study and World Values Survey: Joint EVS/WVS 2017-2021 Dataset (Joint EVS/WVS). JD Systems Institute & WVSA. Dataset Version 1.1.0, doi:10.14281/18241.14.

- Haerpfer, C., Inglehart, R., Moreno, A., Welzel, C., Kizilova, K., Diez-Medrano J., M. Lagos, P. Norris, E. Ponarin & B. Puranen et al. (eds.). 2021. World Values Survey Time-Series (1981-2020) Cross-National Data-Set. Madrid, Spain & Vienna, Austria: JD Systems Institute & WVSA Secretariat. Data File Version 2.0.0, doi:10.14281/18241.15.

Maternal mortality and abortion restrictions

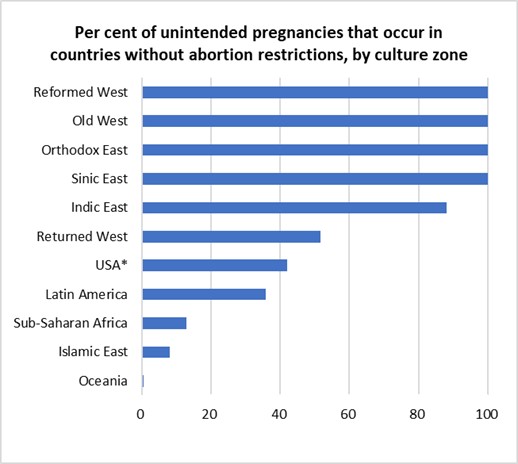

In my previous post, I estimated that 47% of pregnancies are unintended, and of these, 43% occur in countries where abortion is illegal or severely restricted. In countries where abortion is widely available, 71% of unintended pregnancies are aborted compared to 46% in countries with severe restrictions.

The World Health Organization (WHO) estimates that around one-third of the 23 million induced abortions carried out each year in countries where abortion is severely restricted are performed under the least safe conditions, by untrained persons using dangerous and invasive methods. Safe abortion is an essential health care service. It is a simple intervention that can be effectively managed by a wide range of health workers using medication or a surgical procedure. In the first 12 weeks of pregnancy, a medical abortion can also be safely self-managed by the pregnant person at home.

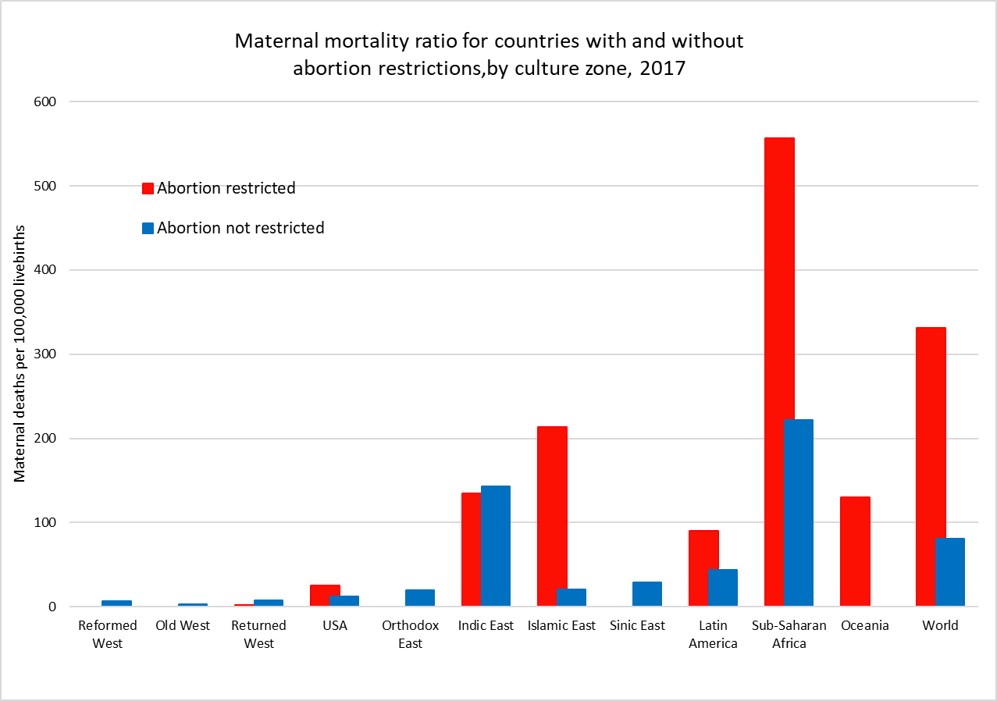

Maternal mortality is defined as death while pregnant or within 42 days of the end of pregnancy from any cause related to or aggravated by the pregnancy or its management. The plot above shows the average maternal mortality ratio (MMR) per 1,000 live births for countries (and US states) grouped by access to abortion and culture zone for the year 2017 (see here for more details).

While countries that restrict abortion have higher MMRs than those that don’t for most of the culture zones, we cannot conclude that abortion restriction per se is responsible for the difference. Abortion restriction is also correlated with other determinants of higher MMR such as lower average income per capita, less access to health care, and higher levels of discrimination against women.

The global MMR has declined from 345 per 100,000 livebirths in 2000 to 212 per 100,000 livebirths in 2017, a 40% decrease in 17 years. There have been substantial declines in MMR in every culture zone except for the Reformed West and Old West where MMR rates were already very low in 2000 and in the USA where rates have risen substantially during the 21st century.

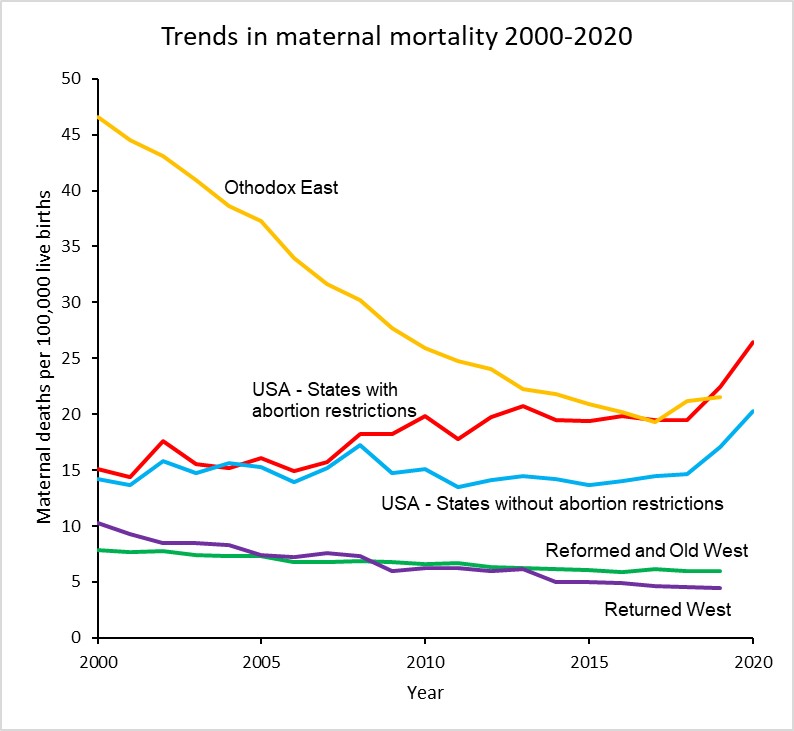

The plot below takes a closer look at MMR trends in the USA, the Reformed and Old West, the Returned West and the Orthodox East. The latter two culture zones include the former Soviet bloc countries. With the exception of Poland in the Returned West, all these culture zones except the USA do not restrict access to abortion services and allow abortion on request or in some countries on “economic and social grounds”.

The maternal mortality ratio for the USA has increased from around 15 per 100,000 livebirths in 2000 to 23.8 in 2020, a 62% increase. Abortion rates in States which now restrict abortion were similar to those in states which don’t until 2008 and afterwards diverged substantially. The rate for states with restrictions was 26.4 in 2020, 30% higher than the MMR of 20.2 for states without restrictions.

There has been considerable controversy about the substantial increase in maternal mortality in the USA, particularly as to whether it is associated with improvements in the identification and reporting of maternal deaths. The addition of a pregnancy checkbox to death records from 2003 onwards is thought to have led to some increase in estimated MMRs in the early 2000s, but several studies have also identified that increasing restrictions on the general availability of reproductive health services have played a major role, particularly in states restricting access to abortion.

Hawkins et al (2019) found that a 20% reduction in the numbers of Planned Parenthood clinics resulted in an 8% increase in maternal mortality and states that enacted legislation to restrict abortions based on gestational age increased the maternal mortality rate by 38%.

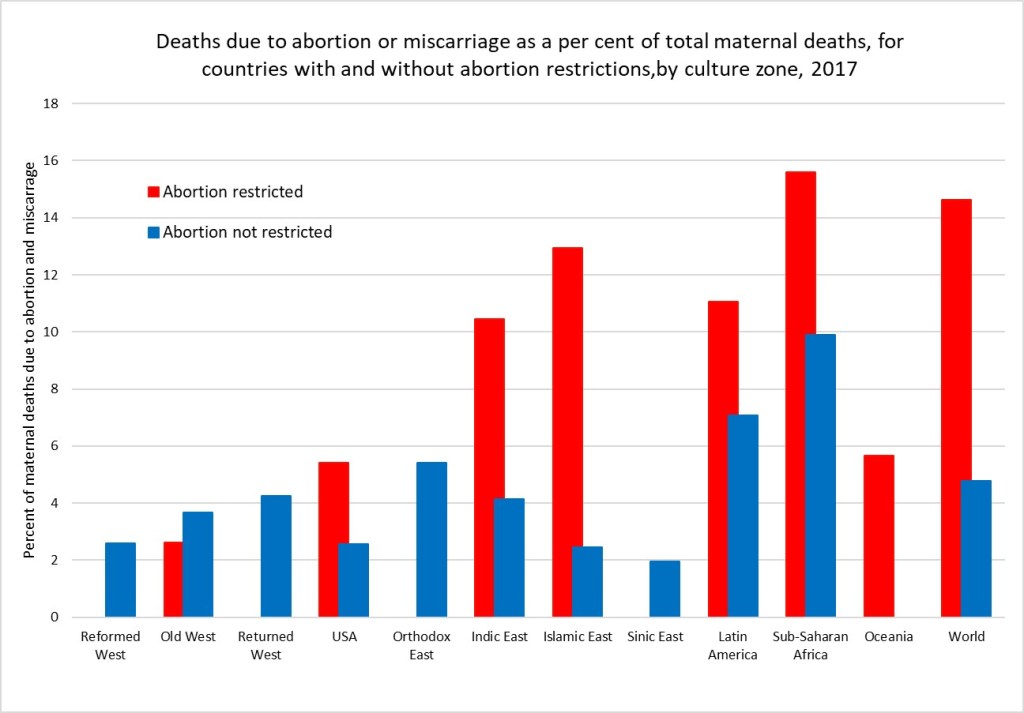

A 2020 study by the Commonwealth Fund compared maternity care in the USA with 10 other developed countries and found that the USA has the highest maternal mortality among developed countries and that there is an overall shortage of maternity care providers (obstetrician-gynecologists and midwives). The USA has 12 to 15 providers per 1,000 livebirths, and all the other developed countries have a supply that is between two and six times greater. Although a large share of its maternal deaths occur postbirth, the U.S. is the only country not to guarantee access to provider home visits or paid parental leave in the postpartum period. In the early 2000s, WHO estimated that unsafe abortion accounted for around 13% of total global maternal deaths, then estimated to be around half a million deaths per year. A more recent study by WHO staff and academic colleagues in 2014 estimated that abortion accounted for 7.9% of maternal deaths at global level between 2003 and 2009. Recent WHO estimates for global deaths by cause do not include deaths due to induced abortion. I have elsewhere used results from the Global Burden of Disease Study 2019 to estimate very approximately the proportion of maternal deaths due to abortion and miscarriage for the period 2015-2019. These would include induced abortion deaths as well as deaths due to spontaneous abortions and miscarriages. The following plot shows the estimated average percent of maternal deaths attributed to abortion and miscarriage for countries with and without abortion restrictions in each culture zone.

Overall, I estimate that there were 75,500 deaths globally due to abortion and miscarriage in 2017 (these include spontaneous events as well as induced abortions). Of these 70,300 were in countries with abortion restrictions. Assuming the rate in countries with unrestricted abortion relates to the spontaneous events, I have estimated that abortion restrictions resulting in unsafe abortions caused 54,350 deaths in 2017. If all abortions were safe, there would have been only 21,200 deaths globally due to spontaneous abortion and miscarriage in 2017.

Its quite possible these very back-of-the-envelope estimates are under-estimates. Classification of maternal deaths due to abortion, and more specifically unsafe abortion, is associated with a risk of misclassification. Even where induced abortion is legal, religious and cultural perceptions in many countries mean that women do not disclose abortion attempts and relatives or health-care professionals do not report deaths as such.

A medical abortion procedure uses the drugs mifepristone and misoprostol which can be taken in pill form up until the 12th week and are very safe. They require no surgery or anaesthesia. These drugs were developed in 1980 and first became available for induced abortions in France in 1987. It became available in the USA in 2000 and is on the WHO list of essential medicines. Cost and availability limits access in many parts of the developing world.

It is usually possible to carry out this procedure oneself at home. During the covid pandemic, a number of countries including the UK have made abortion accessible via an online consultation after which the pills are sent by post to the woman to take at home. The Netherlands-based charity Women on Web aims to prevent unsafe abortions by providing abortion pills to women in countries where safe abortion is available.

In December 2021, the FDA made permanent a covid-era policy allowing abortion pills to be prescribed via telehealth and distributed by mail in US states that permit it.Even before the FDA action,abortions induced by pills rose to more than 54 percent of all U.S. abortions in 2020, according to the Guttmacher Institute. Nineteen states have banned prescription of these pills via online consultation, requiring the woman visit a physician. And of course, in states which severely restrict abortion, this will require a completely unnecessary trip out of state.

Women on Web is making medical abortion available to women in the USA and elsewhere who are facing these restrictions. The cost for a woman to obtain the pills for a medical abortion is 90 Euros, or around 100 US dollars. You can donate to fund abortions for women unable to afford them here. Or to US based abortion funds here.

While legal abortions done under the guidance of a professional are the gold standard. Self-managed abortion can be safe, too, if you have the right information. But as I noted above, the banning of abortion typically goes hand-in-hand with restrictions on contraception and reproductive health services, as well as discrimination and other restrictions on women that result in higher maternal mortality rates, more femicide and abuse, less access to education and employment, and greater female poverty levels.

The removal of a basic reproductive rights for women in the USA is being driven by a minority, many of whom are fundamentalist Christians. According to a recent survey, white and Hispanic fundamentalists are the only religious group in the USA for which a majority oppose the legal availability of abortion (The Economist, May 7, 2022).

I discussed in a previous post how enforcement of social norms governing human fertility have been a major factor in pre-modern religions. For thousands of years, very high levels of child mortality and other survival pressures meant that most societies sought to ensure that women produced as many children as possible and discouraged divorce, abortion, homosexuality and contraception. Additionally sexual behaviour, particularly that of women and that not linked to reproduction, was strongly socially controlled to minimise uncertainty about paternity. Religion was the primary method of social control and pre-modern values regarding women’s rights, reproduction and sexuality are still dominant in most of the major religions, particularly fundamentalist forms. In a world facing overpopulation, global warming, habitat destruction and species extinction, it is crucial that outdated and cruel pre-modern values do not condemn women to reproductive slavery and an inability to control their own fertility, and reduce our ability to address these inter-related crises using all the tools and knowledge now available.

Global variations in abortion legality and rates

Many of us here in Europe and Australia are watching in horror as the US Supreme Court moves towards taking away the reproductive freedom of US women. And from the noises being made by Republican politicians, access to contraceptives, gay marriage and any other human rights not recognized in the 16th century are at risk also.

During my close to two decades responsible for WHO global health statistics, I worked closely with the maternal health department on regular assessments of maternal mortality, including deaths due to unsafe abortion. My team collaborated with the Guttmacher Institute on several occasions to produce global statistics on induced abortion. Given the current situation, I was interested to see that the Guttmacher Institute and WHO released first-ever country-level estimates of unintended pregnancy and abortion (see here) a little under two months ago.

The new study analysed data for 150 countries for the period 2015-2019, and found that:

- Almost half of the 220 million pregnancies globally per year are unintended.

- Six in 10 unintended pregnancies end in an induced abortion (63 million per year).

- Overall, 29% of all pregnancies globally end in an induced abortion.

- Regional averages mask large disparities within regions for unintended pregnancy and abortion rates.

The Guttmacher/WHO study covers 90% of the 1.9 billion women of reproductive age. Almost all the missing countries (because of lack of data) are in the Western Asia and Northern Africa region, most of them Islamic states or with a dominant Islamic culture. I describe elsewhere how I imputed data for most of the missing countries and added data on legal grounds and restrictions regarding abortion. Countries classified as having abortion restrictions are those which completely prohibit abortion or allow abortion only on one or more of the following grounds: risk to life, risk to health, rape or fetal impairment. Countries classified as without abortion restrictions also allowed abortion on social or economic grounds, or on request. Given the polarization of the US states in allowing or restricting abortion, I also used information from Planned Parenthood to classify US states into two groups with and without restrictions.

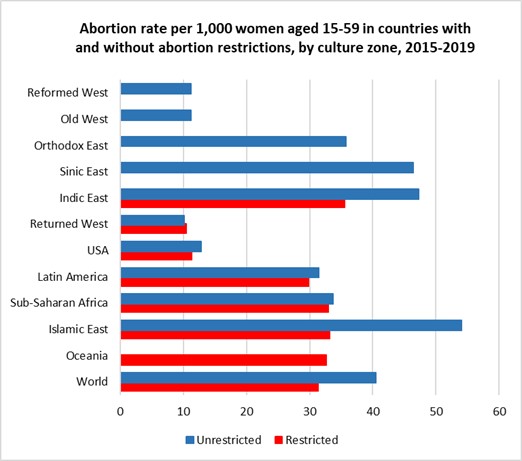

First, a brief overview at the global level of the differences between grouped countries with and without restrictions:

- 36% of women of reproductive age live in countries with restricted access to abortion. These countries account for 33% of global abortions, 50% of global live births and 81% of global maternal deaths.

- The global abortion rate per 1,000 women aged 15-49 years is 31 for countries with restrictions and 41 for countries without restrictions.

- 21% of pregnancies are terminated by abortion in countries with restrictions, 34% in countries without restrictions.

- Average GDP per capita (purchasing power parity dollars) was $18,300 in countries without restrictions, and 71% of women aged 15-49 used modern forms of contraception. For countries with restrictions, the average GPD/capita was $8,500 and only 57% of women used modern forms of contraception.

- Countries restricting abortion were much more religious with 66% of adults attending religious services at least once a month, compared to 27% in countries not restricting abortion (data on religious practice from the World Values Survey and European Values Study, see earlier post here).

These global averages conceal very large differences across regions, and between countries in some regions. I have examined these patterns by grouping countries into 11 culture zones, based on those developed by Welzel (2013) for the World Values Survey.

I modified the culture zones slightly, to include Canada in the Reformed West and keep the USA in its own separate category. I also moved predominantly Muslim countries from “Indic East” and “Sinic East to group together all countries with a predominantly Islamic culture and values. See here for full definitions of the culture zones.

The left-hand figure 1 shows that abortion is universally legally available in most of Europe, Canada, Australia and New Zealand, in the Orthodox and Islamic countries of the former Soviet-bloc and in the non-Islamic countries of Asia. It is legally severely restricted in most Islamic countries and sub-Saharan Africa. Abortion rates are substantially lower in the high-income countries of Europe, North America and Australia and New Zealand than in the Asian regions where abortion is unrestricted AND in the countries in all developing regions irrespective of whether abortion is legally restricted or available. Note that USA results have been calculated by grouping States into those with and without significant abortion restrictions.

For 2015-2019, almost half of unintended pregnancies (46%) were aborted in countries where abortion was restricted (often severely) and a little over two-thirds (70%) in countries where abortion is accessible. In the three regions where around 40-50% of women with unintended pregnancies have restricted access to abortions, overall abortion rates per 1,000 women of reproductive age differ by less than 2 abortions per 1,000 from those in countries (or US states) without restrictions. These are the USA (11 versus 13 per 1,000), the Returned West (11 versus 10 per 1,000) and Latin America (30 versus 31 per 1,000). The Returned West consists of former Soviet-bloc countries that have joined the EU, and the largest of these, Poland, is the only one to have restricted abortion, prohibiting it for fetal impairment, economic or social reasons, or on request.

People seek and obtain abortions in all countries, even in those with restrictive abortion laws, where barriers to safe abortion care are high. In fact, over the past three decades, the proportion of unintended pregnancies that end in abortion has increased in countries that have many legal restrictions in place. The figures presented above suggest that the illegalization of abortion will not substantially reduce its incidence. Over recent decades, most of the changes to the legal grounds for abortion have been in the direction of recognizing women’s rights to reproductive autonomy (recent examples include Ireland, Argentina, Mexico and Columbia).

The increasing restrictions in the USA are one of the few examples of major reductions in women’s rights occurring outside the Islamic countries. In the case of the USA, these changes are to rights that women have had for half a century and are being driven by an anti-democratic coalition of white nationalists and religious extremists who do not represent the majority views of the population. A recent issue of the Economist identified white evangelicals as the one major religious group with majority opposition to the legal availability of abortion (The Economist, May 7, 2022). A majority of Catholics, mainline Protestants and those with no religious identification think that abortion should be mostly or always legal in the USA, and support is over 75% for Jewish, atheists and non-religious with college education.

The rhetoric of some US extremists, and actions already taken to restrict health insurance coverage for contraceptive use, suggests that further restriction on abortion access may well also be accompanied by further reductions in contraceptive availability. The unintended pregnancy rate may well increase, resulting in an overall increase in numbers of abortions occurring, even if the restrictions reduce the percentage of unintended pregnancies that end in abortion. In my next post, I will examine differences in maternal mortality across countries and the extent to which they are associated with legal restrictions on abortion.

Reading Mary Beard on Rome and Hannah Arendt on totalitarianism

Mary Beard covers what she calls the first thousand years of Roman history from around 753 BCE, the traditional date of the founding of Rome by the mythical Romulus and Remus, through to 232 CE when the Emperor Caracalla made every single free inhabitant of the Roman Empire a full Roman citizen. Unlike many histories which focus on the so-called decline and fall of the Roman Empire during the following period through to around 476 CE, when the Gothic Odoacer deposed the last Emperor and declared himself King of Italy, Beard attempts to examine the question of how one tiny and unremarkable Italian village became so dominant a power over so much territory in three continents.

Continue readingIn recent weeks, I’ve been reading SPQR: a history of Rome by Mary Beard (2015) and simultaneously dipping into the classic The Origins of Totalitarianism by Hannah Arendt (1951). Hannah Arendt in much slower going and about halfway into SPQR I became so engrossed I just binge read to the end.

Mary Beard covers what she calls the first thousand years of Roman history from around 753 BCE, the traditional date of the founding of Rome by the mythical Romulus and Remus, through to 232 CE when the Emperor Caracalla made every single free inhabitant of the Roman Empire a full Roman citizen. Unlike many histories which focus on the so-called decline and fall of the Roman Empire during the following period through to around 476 CE, when the Gothic Odoacer deposed the last Emperor and declared himself King of Italy, Beard attempts to examine the question of how one tiny and unremarkable Italian village became so dominant a power over so much territory in three continents.

Continue readingNear-Death Experiences – Part 1

I’ve had a number of near-death experiences over the years. Almost all of these were the result of sheer stupidity doing risky things. I recently read an account by someone who survived having seen certain death approaching. That and other recent circumstances have got me thinking about my own experiences and meditating on death and dying more generally.

In this post I remember two incidents in which I was knocked unconscious and would never have known about it if I had died. These experiences had a far greater impact on me and my feelings about death and dying than any of the incidents where I realized that death was a probable outcome.

In the early 2000s, I was in South Africa for three weeks as one of the staff for a WHO global training course. The course was being held in a small game park and resort, which was closed to general visitors. There was a water slide which was also closed, but several of us persuaded the staff to open it one lunch time for us. The water slide was a fully enclosed tube with water running through it which ended over a small swimming pool about 2 metres deep. My friend J and I were the first two there and each did a slide down the tube. I sat up in the tube and found there was too much friction so that I went down quite slowly.

For my second slide, I lay down completely flat in the tube. I do now remember the initial moments, going quite fast and bouncing around in the tube. I must have hit my head on the side of the tube on the way down because I was unconscious when I entered the water and went to the bottom of the pool.

J had gone down before me and was already walking back up the path to the top of the slide. Halfway up he looked back and saw me lying on the bottom of the pool. He initially thought I was clowning around and kept walking. But when he looked back again, I was still in the bottom of the pool. He ran back down to pull me out of the water. I was bleeding heavily from a cut over one eye, and he told me later he thought my skull was broken and my brains were coming out. I regained consciousness a few minutes later, I don’t know whether he did resuscitation or I started breathing on my own. I asked him what happened and where was I. When he told me we were in South Africa, I was astonished. I had no memory of going to South Africa or any idea why I would be there. I was as astonished as if someone had just told me I was in Siberia. I knew who I was and who J was, but I had no memory of anything that had happened in the last few weeks.

An ambulance came, and I was taken to the nearest town with a hospital, where they took X-rays of my head and neck. And debated for some time whether the signs of fractures in my neck vertebrae were new or old (they were old). I was fitted with a neck brace and they stitched up the split skin over one eye. My amnesia gradually disappeared over a period of a day or so, until eventually I could remember the initial part of going down the slide and starting to oscillate. But the actual blow to the head and the aftermath before I came to has remained a blank.

It was an existential shock to realize that if I had not been pulled out, but drowned, I would never have known. I would not have known I was about to die. Amnesia meant my mind was a blank in the minutes leading up to possible death. It was profoundly disturbing to realize it was entirely possible I would die without ever knowing about it. And it continues to be a realization that I keep revisiting.

I also realized that the state of being dead is nothing to fear. I experienced “not being there” in any form and its nothing at all to be afraid off. You don’t exist, and there is nothing to experience the not existing.

The second experience occurred a couple of years later in Geneva. I had left work to ride to the gym on my bicycle. I was riding in the bus lane on a road which went down a long slope from the World Health Organization. I was riding quite fast and became worried that a bus might be coming up behind me. I looked back and in doing so steered the bike into the gutter. I hit the gutter at speed and went over the front handlebars.

That is the last memory I have until I suddenly became aware that I was on my bicycle and covered in blood. I was bleeding quite profusely from skin loss on legs and arms and riding in heavy traffic. I had no idea where I was at all but knew from my injuries that I must have been in some sort of accident. I got off the bike and rang my wife on my mobile. I explained I had been in an accident and had no idea where I was. She told me to go to the nearest street corner and tell her the names of the streets. I did that and it turned out I was near the main train station about three and a half kilometres from where the accident occurred.

She came and got me and took me to the hospital, where they diagnosed concussion (duhh!), cleaned and bandaged my wounds, and kept me overnight under observation. When I returned to work and told colleagues what had happened, one of them told me he had seen me on my bicycle riding in the traffic and had not noticed anything unusual. Apparently I am capable of riding in traffic while unconscious. Or perhaps conscious but without any memory-retention ability. I could easily have ridden in front of a car and been killed. As with the first experience, if that had happened I would never have known.

I guess death was a more certain possible outcome for the South African experience. If my friend had not seen me on the bottom of the pool and got me out in time, I would have almost certainly died. This was a much more traumatic experience (after the event) than other “near-death” experiences where I was conscious and realized I was likely to die. I’ll write about them in a later post.

I recently read a blog post by Nathan Hohipua in which he argues that it is impossible to (truly) imagine our deaths, and that the only possible attitude towards death is one of anxiety. He claims that “The light of consciousness cannot really, truly imagine its own extinction” and concludes that “Anxiety is the only possible response to death because it’s just what it is to contemplate something that literally can’t be contemplated because it is the end of all possibility of contemplation.“

I think he is wrong in generalizing his own inability to imagine the state of being dead to others. In the waterslide accident, I truly feel that I came back from an experience identical to that of being dead. No memory, no awareness, no experience, nothing. If I had not come back, I would never have known it. That realization has been profoundly disturbing. But the state of being dead? I experienced “not being there” in any form and its nothing at all to be afraid off. You don’t exist, and there is nothing to experience the not existing. I may be missing something, but I don’t have any problem accepting that there will be a future point after which I simply don’t exist. Its exactly the same as before the point in time at which I started to exist (some time after conception). I have not existed for billions of years and I will also not exist for billions more.

The process of gradually losing function and experiencing pain and possibly loss of mental functioning, whether through ageing or illness, that is a completely different issue. And something that does worry me. I am working on accepting and letting go of the mental drama about it. And eventually when needed, do some contingency planning and prepare a living will. Nathan Hohipua says that if someone tells you they have completely accepted their death, they are deceiving themselves. That likely is true in some cases. And might be true if you are referring to the process leading up to the point of death. But completely untrue for me, if you are referring to the state of being dead. I’ve experienced it, and its nothing to be afraid of.

Values and religion in 2020: an updated map

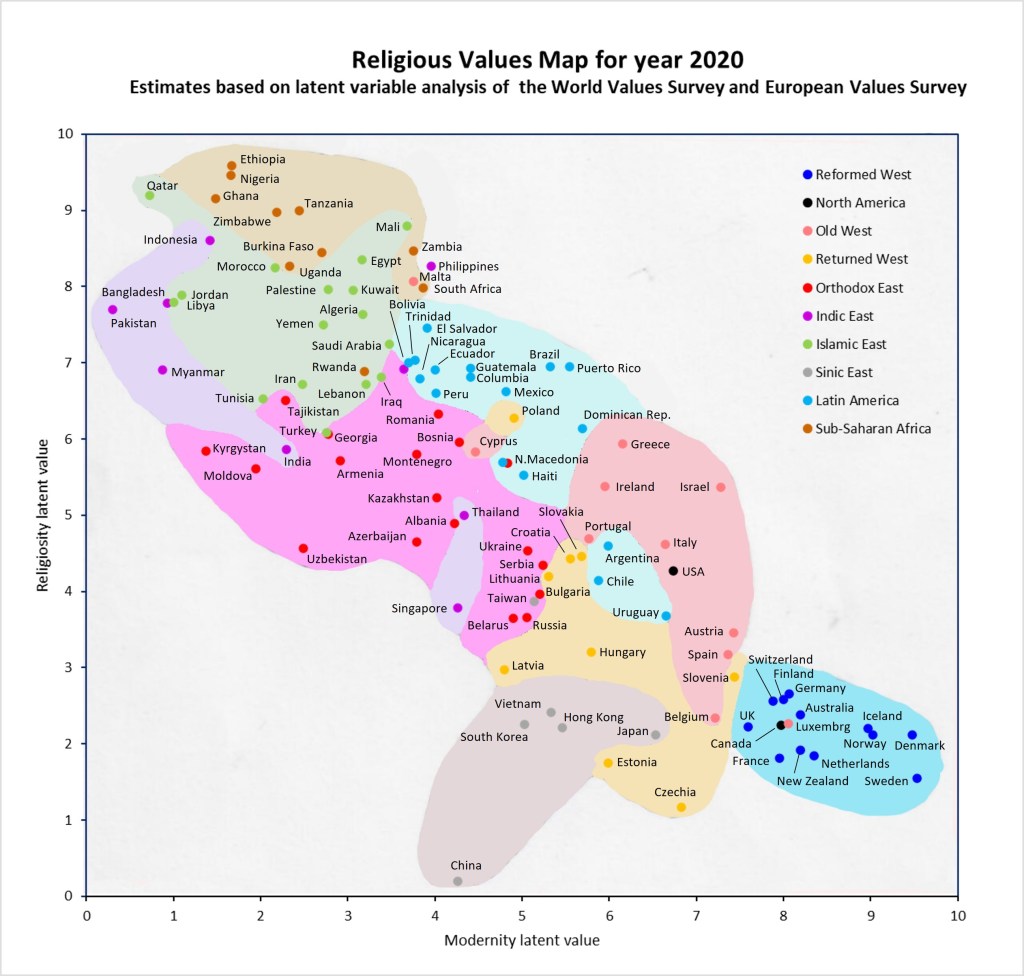

In my previous post, I presented updated estimates of trends in average religiosity and religious values for 110 countries using latent variable analysis of data from the World Values Survey and European Values Study [1-4]. The map below plots these countries according to their latent variable values for modernity (horizontal axis) and religiosity (vertical axis) in the year 2020. The colours indicate culture zone and the shading roughly indicates the main domain of countries in each culture zone. Moving downwards to the right on this graph indicates increasing modern values and decreasing religiosity. The inspiration for this map presentation was the culture zone maps produced for earlier waves of these surveys by the political scientists Ronald Inglehart and Christian Welzel [5]. The culture zones are defined in a previous post here.

Apart from the uncertainty in these values resulting from survey sample size limitations, differences in the ways surveys were administered, and differences in translation and cultural understanding of questions, there is also statistical uncertainty in the latent variable estimation process. Not too much should be made of small differences between countries, and I focus on the broader patterns.

The degree of premodernity of religious values is fairly similar for the Islamic East and Sub-Saharan Africa, but the African region is somewhat more religious than the Islamic region. The Indic East has higher levels of premodern values than either of these regions. One manifestation of this is the current rising level of Hindu nationalism in India along with the violent persecution of Indians of other religions. The degree of modernity of values is similar for the majority of Latin American countries and the former Soviet bloc countries, but religiosity is significantly lower in the latter, where religion is largely a marker of national identity and most are non-practicing.

The North America culture zone includes only two countries, the USA and Canada. It is clear from the map that Canada belongs with the Reformed West countries in contrast to the USA, which sits in the Old West zone close to Italy, and also not far from three South American countries: Argentina, Chile and Uruguay. Malta and Cyprus are also outliers for the Old West culture zone, with higher levels of religiosity and less modern values. Along the decreasing religiosity-increasing modernity axis, Qatar is at the top end and Sweden at the bottom end. China is an outlier to the lower left, with the lowest level of religiosity of all the countries, but also a modernity value towards the middle of the scale between modern and pre-modern.

It should be emphasised that this map reflects national averages for individuals and may not be reflected in laws and form of government. Increasingly authoritarian regimes across the world are imposing values that a substantial proportion of their population do not accept. The USA has a growing proportion of the population rejecting democracy in favour of minority rule and the restriction of various rights particularly for women and minority voters. Unhappiness with the results of neoliberal economic and social policies over recent decades has been successfully redirected into “values wars” rather than addressing the real causes of declining average incomes and reductions in social safety nets along with the reduction of taxation and regulation for high income individuals and companies.

References

- Inglehart, R., C. Haerpfer, A. Moreno, C. Welzel, K. Kizilova, J. Diez-Medrano, M. Lagos, P. Norris, E. Ponarin & B. Puranen et al. (eds.). 2014. World Values Survey: All Rounds – Country-Pooled Datafile Version: https://www.worldvaluessurvey.org/WVSDocumentationWVL.jsp. Madrid: JD Systems Institute.

- Haerpfer, C., Inglehart, R., Moreno,A., Welzel,C., Kizilova,K., Diez-MedranoJ., M. Lagos, P. Norris, E. Ponarin & B. Puranen et al. (eds.). 2020. World Values Survey: Round Seven–Country-Pooled Datafile. Madrid, Spain & Vienna, Austria: JD Systems Institute& WVSA Secretariat[Version: http://www.worldvaluessurvey.org/WVSDocumentationWV7.jsp].

- Gedeshi, Ilir, Zulehner, Paul M., Rotman, David, Titarenko, Larissa, Billiet, Jaak, Dobbelaere, Karel, Kerkhofs, Jan. (2020). European Values Study Longitudinal Data File 1981-2008 (EVS 1981-2008). GESIS Datenarchiv, Köln. ZA4804 Datenfile Version 3.1.0, https://doi.org/10.4232/1.13486.

- EVS (2020): European Values Study 2017: Integrated Dataset (EVS 2017). GESIS Data Archive, Cologne. ZA7500 Data file Version 3d. WVS. Archived from the original on October 19, 2013.

- Ronald Inglehart; Chris Welzel. “The WVS Cultural Map of the World”. WVS. Archived from the original on October 19, 2013.

The Order of Time – Carlo Rovelli

When I studied physics at university in the 1970s, I became interested in the nature of time, particularly in light (pun intended) of its role in both special and general relativity. I also read The Direction of Time by Hans Reichenbach (1891-1953) regarded as the leading empiricist philosopher of the 20th century, as well as other philosophers and writers. Later, in the 1990s I became a student of Zen Buddhism with Hogen Yamahata, who emphasised that the only reality is what is experienced here-now. This certainly describes my experience of time but is also fundamentally at odds with the usual understanding of the implications of modern physics.

So I read Carlo Rovelli’s fourth book The Order of Time (2018) with great interest. Unusually for a physicist he gives an accessible and very readable overview of the main findings of physics but also discusses the human experience of time and tries to integrate our common experience with the insights of modern physics. See here for my previous review of his first book Anaximander.

It’s a short book and is written for a lay audience, written in a very readable and accessible way. Its been criticized by some for not having enough hard science exposition and too much speculative stuff, particularly in the third section. However, I thoroughly enjoyed the mix and wholeheartedly recommend it if you are at all interested in the nature of time.

Rovelli opens with the claim that the nature of time is perhaps the greatest remaining mystery. I’m inclined to think that consciousness and the fundamental constituents of reality are equally great mysteries, and indeed these may all be interrelated. The introductory chapter identifies a number of key questions about time:

- Does the universe unfold into the future, as time flows? Does in fact time “flow”?

- Does the past, present and future all exist in the block universe of relativity, with our consciousness or perhaps the “present moment” moving through the blocks?

- Why do we remember the past and not the future? Put another way, why does time flow only in one direction, when the fundamental equations of physics have no preferred time direction?

- Is time a fundamental property of the universe in which events play out, or is time an emergent property, perhaps emerging only at a certain scale or degree of complexity?

The rest of the book is divided into three parts. In the first part, Rovelli summarizes the understanding of time in modern physics, and how this is radically at odds with our normal perceptions of time. Special and general relativity have conclusively shown that there is not a single universal time. Time passes at different rates at different places (faster where gravity is lower) and at for observers travelling at different speeds (slower when velocity is greater). Additionally, there is no longer a single universal “now”. Between the past and the present there is an expanded “now” in which different observers will see events occurring with different time differences and possibly in a different order. The direction of time, the difference between past and future, does not exist in the elementary equations of the world and appears only in the second law of thermodynamics (entropy of a closed system can only increase or stay the same).

The second part, The World Without Time, delves into the fundamental nature of reality, drawing on Rovelli’s own field of research, loop quantum gravity in a shorter section. He argues that the fundamental constituents of reality are events (interactions) not things, and that space and time are emergent properties from these interactions. This is controversial, quantum loop gravity is but one of a number of contenders for the ’Theory of Everything’. There are physicists such as Lee Smolin (The Singular Universe and the Reality of Time) who have argued the opposite: that time is indeed a fundamental property of the universe. And more, like Sean Carrol, who conclude that neither he nor anyone else has a clue whether time is fundamental or emergent.

The third and final part attempts identify the sources of time and to understand how the non-universal time of relativity and the non-time of fundamental physics are consistent with our experience of time: “Somehow our time must emerge around us, at least for us and at our scale.” This to me was the most interesting and inspiring part of the book, though there are many reviewers on Amazon and Goodreads who really did not like it. Rovelli is up-front about the speculative nature of his “possible” answer. He is not sure it is the right answer, but it’s the one that he finds the most compelling and he doesn’t think there any better ones.

As have many before him, Rovelli locates the arrow of time in the second law of thermodynamics, that entropy can never decrease. Entropy is a macroscopic property of systems and essentially associated with the number of microscopic configurations that are consistent with the “blurred” macroscopic view. Rovelli repeatedly uses the idea of “blurring” to explain the emergence of time at the macroscopic level. You have to read him to (possibly) understand it. He also identifies another potential source of temporal ordering in the quantum uncertainty principle; that the values of variables such as speed and position depend on the ordering of their measurement. He then states that Alain Connes has shown that the emergent thermal time and quantum time are aspects of the same phenomenon. Time emerges from our ignorance of the microscopic details of the world.

Although I studied statistical mechanics, I never understood until reading Rovelli that entropy was a relative quantity, determined not only by the state of a system but also by the set of macroscopic variable with which it is observed. Rovelli addresses the issue of why the universe started in a low entropy state (allowing the emergence of time) by suggesting that the universe has pockets of high and low entropy by chance, and necessarily it is only in the regions with low entropy that time can emerge so that life is possible, together with evolution, thought and memories of past times. He is arguing an astonishing variant of the weak anthropic principle, namely, that the flow of time is not a characteristic of the universe as a whole but necessarily associated with local region(s) in which entropy is initially low. This suggested to me that perhaps there might be sentient life forms evolve in local regions of the universe which are not in initial low entropy state according to the macro-variables by which we and other earthly life interact with reality, but may be low entropy for life forms which interact via a different set of macro-variables.

Rovelli goes on to speculate that the emergence of time may have more to do with us than with the cosmos per se. Is this dangerously close to putting humans back at the centre of the universe? He then discusses how causality also is a result of the fact that entropy increases. This is what allows past events to leave traces in the present, and that we remember the past but not the future. Evolution has designed our brains to use the traces to predict the future. Causality, memory, history all emerge from the fact that our universe was in a particular state of low entropy in the past. That particularity is relative, dependent on the set of macroscopic variables with which we interact with the world.

And in the final chapters of the book, Rovelli turns to us, and the role we play with respect to time. This for me was the most fascinating and inspiring part of the book. Rovelli argues that humans (and the rest of the biosphere) have been hard-wired by evolution to accept and use the concept of time. The changing interactions are real, but the time in which all this seems to occur is a manifestation of the human (and probably animal) mind, which has evolved to make use of the memory traces of the past to predict the future. The movement is real, the changing is real, but the time in which all of this seems to occur is nothing more than a manifestation of human (possibly animal) mind and the illusion, in turn, is supported by the entropy generated in the functioning of our brains.

From his discussion of the three sources of time, he draws a number of conclusions about the implications for us:

- The self is not an enduring entity, but an emergent construct of the brain and memory, time is the source of our sense of identity.

- Reality is made up of processes or interactions not things. Things are impermanent.

- Being is suffering because we are in time, impermanent. “What causes us to suffer is not in the past or the future: it is here, now, in our memory, in our expectations. We long for timelessness, we endure the passing of time: we suffer time. Time is suffering.”

Rovelli explicitly notes how these are also some of the key insights of Buddhism: suffering, no-self, emptiness and impermanence. Rovelli here is NOT doing what people like Fritjof Capra and many new age gurus do: to use the strangeness of reality at quantum level as a justification for believing in macroscopic-level things like telepathy or clairvoyance. Rather, he is arguing that his understanding of time is consistent with what I consider some of the most important insights of Buddhism. I have also realized that the lack of a universal present moment is not inconsistent with the Zen insight that only the present exists. My teacher Hogen-san has always used the phrase “here- now” to describe our only reality, not just “now”. So there is no conflict with the time of relativity.

While Rovelli addresses my key questions about the nature of time, I am not convinced of all his arguments and explanations, or even that I fully understand them. But it is an immensely thought-provoking read, and I will read it again and hopefully my brain will hold off hurting long enough for me to clarify my own thoughts and speculations on the nature of time. In the meantime, I have been paying attention to the present moment as much as I can during my daily zazen, trying to simply experience here-now without thoughts about the past or speculations about the future.

Modern and pre-modern religious values: an update

In a recent post, I presented revised estimates for trends in the prevalence of atheism and religiosity for 110 countries over the last 40 years. This was based on a new analysis of the 2021 release of combined data for the WVS and EVS in the Integrated Values Surveys (IVS) 1981-2021 [1, 2]. The main revision to the dataset was to correct an error in the data for the USA. This post summarizes my updated analysis of modern and pre-modern religious values and for the first time I have also carried out an analysis of time trends from 1980 to 2020. See here for full details of the construction of a revised latent variable for modern values and the analysis of time trends.

My earlier post discusses in some detail the conceptualization and operationalization of modern and pre-modern religious values. I here give a very brief overview of this in terms Kohlberg’s three stages of moral development. Stage 1 moral values focus on absolute rules, obedience and punishment and an individual is good in order to avoid being punished. In stage 2, the individual internalizes the moral standards of the culture and is good in order to be seen as a good person by oneself and others. Moral reasoning is based on the culture’s standards, individual rights and justice. In stage 3, the individual becomes aware that while rules and laws may exist for the greater good, they may not be applicable in specific circumstances. Issues are not black and white, and the individual develops their own set of moral standards based in universal rights and responsibilities. As moral values evolve through the three broad stages, the size of the in-group (“us”) with which an individual identifies typically expands from tribe to ethnic group or nation to all humanity.

Continue reading